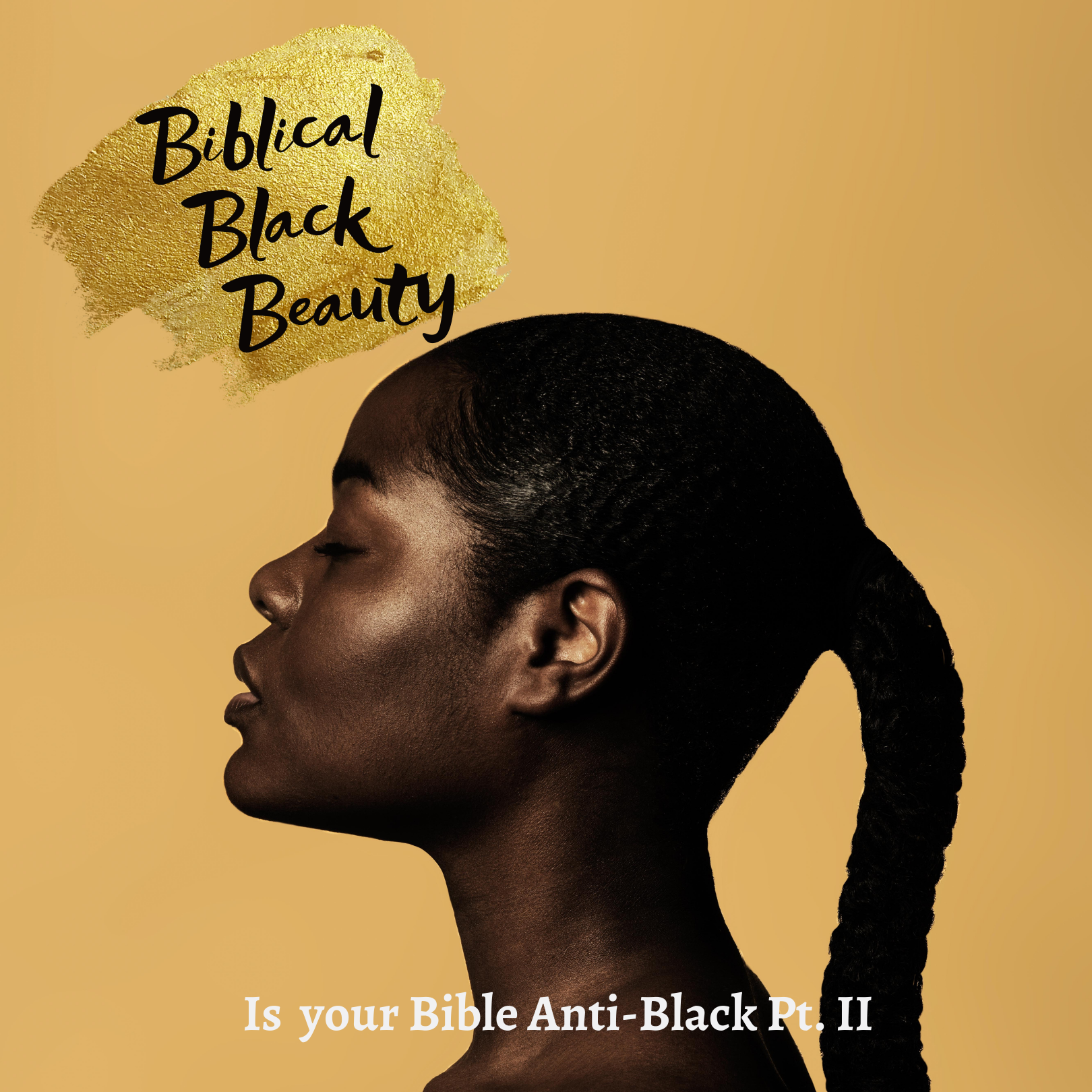

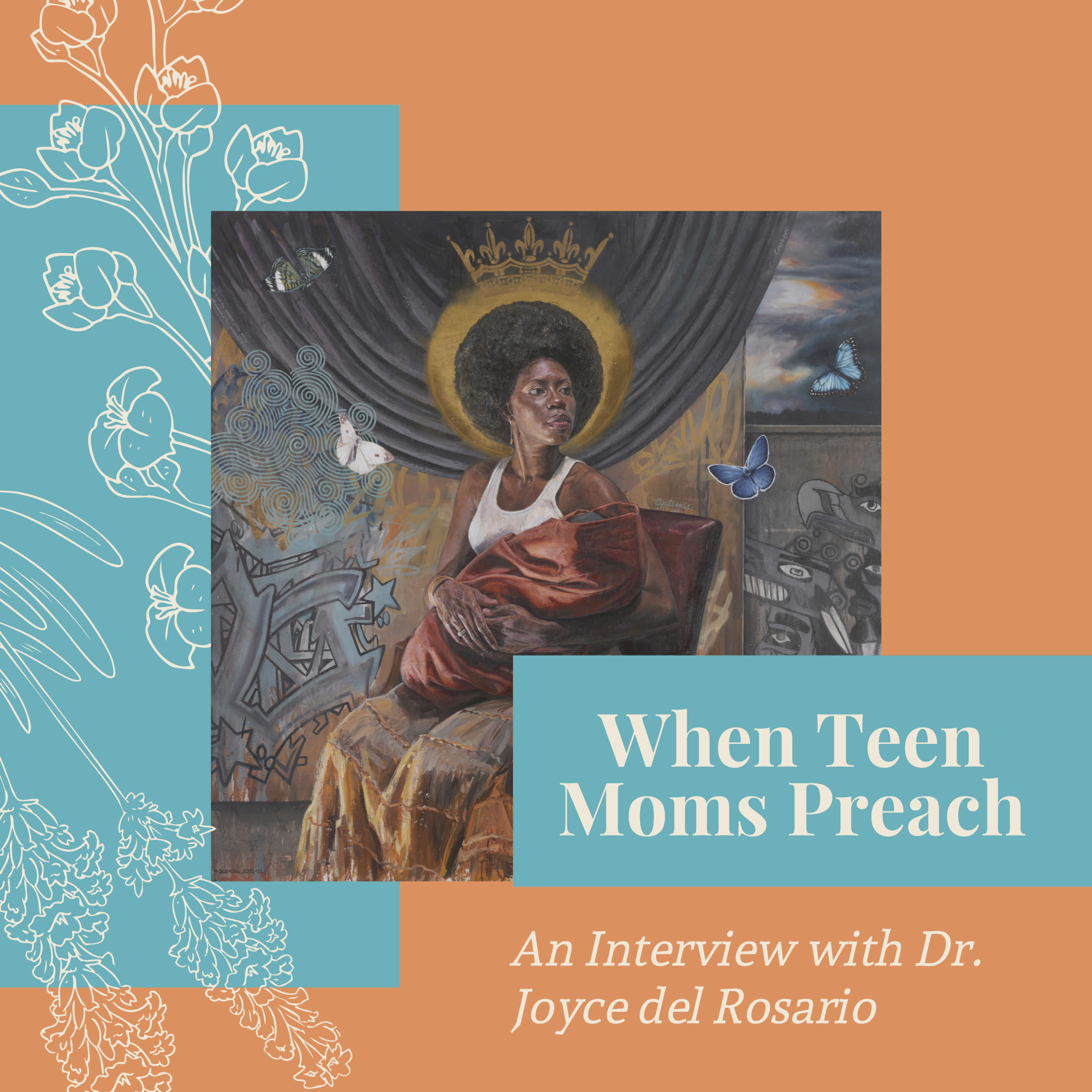

Courage 3.0 is a painting emulating the traditional iconography of Mary. The classic elements are present. The subject is a young woman holding a baby. Her eyes register a resolute purpose of being. She is a mother, yet she is the sole adult in the image, and she looks strong. Around her head is a bright brimming halo with a crown to make even clearer her stately status. However, there is something decidedly different about this image of Mary. At first glance you might reject a likeness of the mother in this painting to the Mary we have grown accustom to. This is because Okomara’s Mary is a dark colored girl, donning an afro and surrounded by graffiti. “It was the most beautiful picture of Mary I had ever seen,” del Rosario explained, “she looked like the teen moms I knew.” This Mary looked both fierce and restless, courageous and vulnerable. She was a Mary with whom del Rosario was familiar.

“Icons,” Joyce reminds us, “transcend our human constructs like race and class.” It became clear, that this was her bridge. Contemporary icons that emulated this marginalized, Jewish teen mother would give her teen theologians the passage to preach. She would use icons to help bridge the chasm of biblical literacy. Historically, when the majority of people were illiterate, the masses looked to art and icons to connect to God. For centuries, the faces of icons stained in glass and lit by light was where God met the poor, marginalized and uneducated. Icons in stained glass windows was how God spoke for generations; they were the filter between the earth and the sky.

Icons, then, were what del Rosario would use to bridge the gap of the marginalized and the educated. Through them she found she could democratize religious power, by giving those who are often passed by in the church, the marginalized teen mother, the pulpit to speak. By making this the content of her dissertation, Rosario would bring to light both in the academy and whatever pulpit she was offered, the message of these young teen moms. Thus, for her dissertation research, del Rosario curated a collection of contemporary images of Mary and selected her focus groups: Teen mothers and the Women who mentor them.

What she found humbled her. While the Mentors were immediately aware of the iconology of Mary emulated through the images, the Teen Mothers were unaware of this fact. This, del Rosario explained, created very different insights. The Mentors, conditioned by an image of a Virgin Mary produced an almost recycled list of insights on the Mary they felt familiar with, even though the Mary shown to them was radically and racially different. The Teen Mothers, on the other hand, unconditioned and free from a conventional list of “right” ways to see Mary, described a woman who was like them: human, stuck in a hard position, ready to fight to the death for the baby she held, tired, alone, and resolved to rise to the position in which she found herself. This was the Mary that the Teen Mothers of questionable circumstances and racialized realities preached. Arguably, this is the Mary whom the church must refamiliarize herself with, because it is only then that we can see her Son for who he truly is: the brown, poor, and marginalized Son of God, born of a teen mom.

In her final comments, Rosario labored to communicate that we should stop assuming that we as evangelicals “bring Jesus to the margins”. “Jesus,” she expressed, “already exists in the margins!” He was, after all born there. She concluded our interview asserting that it is not about “giving the margins Jesus”, but rather, “it is about seeing the Jesus the margins already know.”

The work that Dr. Joyce del Rosario dedicated her academic life to is work that we should all strive to incorporate in our churches. It is the work of centering the margins—of allowing a teen mother to preach.