“True Peace is not Merely the absence of tension, it is the presence of Justice.”

Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Cradle of the Confederacy and The Birthplace of The Civil Rights Movement

Cities, like people, have complicated histories. Their character can reflect apparent contradictions, but if we take them as a whole we see their beauty. Cities bear the marks of who we were, and in remembering, they give us the opportunity to decide who we will be in the future. Montgomery is one of those cities. Its seal is a jarring reminder of paradoxical truths. Montgomery is both the “Cradle of the Confederacy” and the “Birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement.”

The city is still home to the First House of the Confederacy, but thanks to the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), it now has the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. The EJI is founded and directed by Bryan Stevenson, author of Just Mercy. They work to provide legal services to prisoners. We’ve been interested in their work for some time and recently visited their new public exhibits. Here are some photos that highlight the power of the memorial.

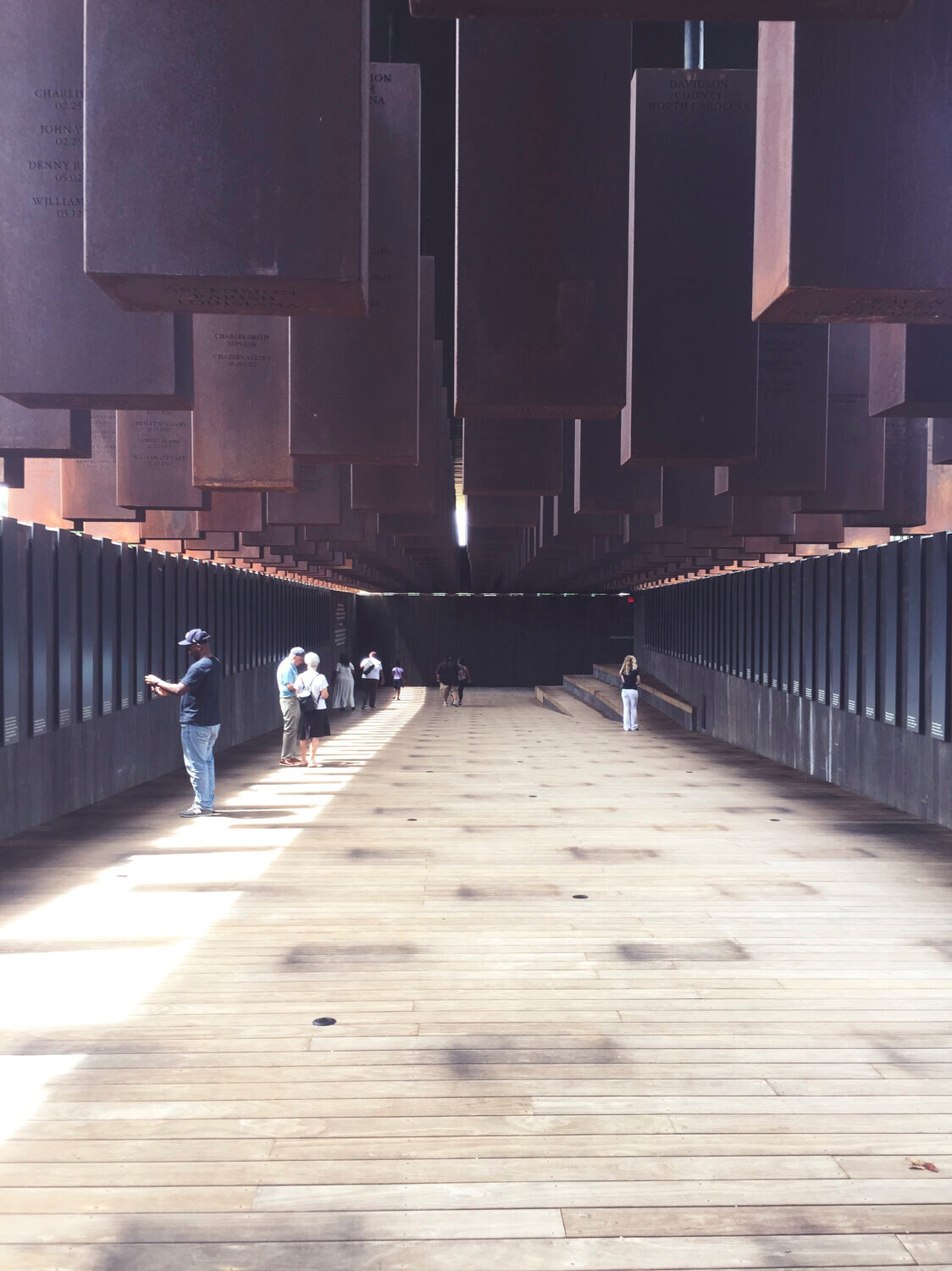

“The centerpiece of [the memorial] is a sprawling wood-and-metal open-air structure featuring 800 6-foot columns, each one representing a county where a lynching took place in the United States between 1877 and 1950.”1 The EJI worked over six-years to recover the history of the public murders, documenting 3,959 lynchings across the south.

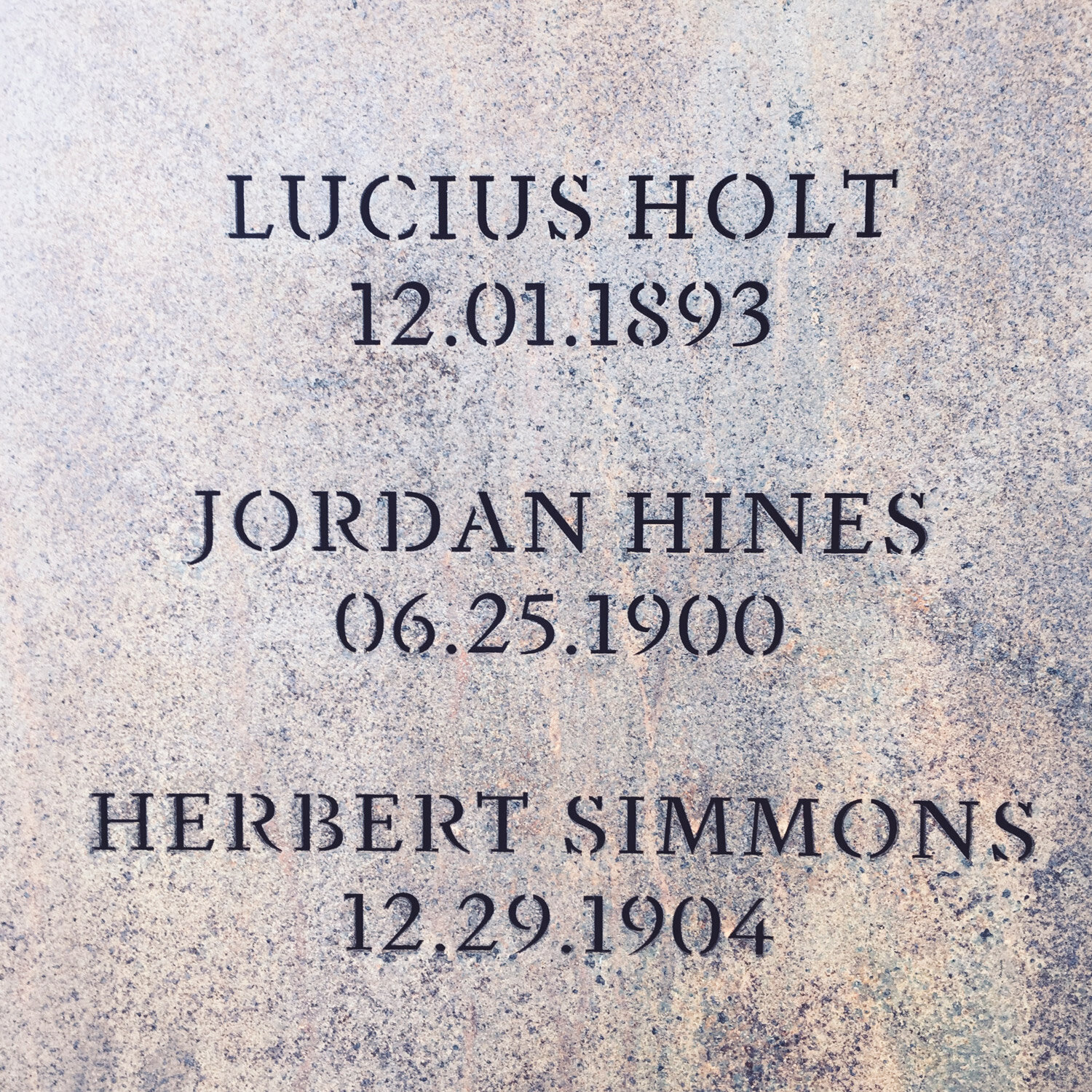

Etched in each of the 800 columns are the names of lynching victims. “None of the columns are telling exactly the same story—made of corten steel, an alloy that changes hue when exposed to air, they’ve each morphed to a different shade of brown over time.”2 Several times, the records are so incomplete, the column reads “Unknown” in the place of the name.

At the memorial entrance the columns are eye level. Victor Luckerson captures the effect of the memorial as one moves further into its heart. He writes, “As you wind your way through the memorial, the floor slopes downward and the eerie symbolism of a cluster of human-sized columns suspended by metal poles becomes more apparent. Eventually, the columns stretch too far in the air to clearly read the names, so the viewer can only assess them in aggregate. The terror of lynching becomes mass spectacle, as it was when it was happening across the South less than a century ago. The structure evokes the haunting photo of a mutilated black body hanging over a crowd of white onlookers, but turned upside down.”3

After looking at these pictures, consider the Town Fabric concept. Town Fabric is the quality of the city that distinguishes it as a distinct place for human interaction. Town Fabric is the setting-ness of the city. It distinguishes the city as a place for a particular story. It can be broken down into three essential functions, the first being exemplified by Montgomery. Town Fabric

Creates settings for monuments

Houses people and provides places for work and their private needs

Shapes and defines the outdoor public spaces of a town/city4

The first function highlights the importance of The National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Monuments and memorials are a product of civic art. The purpose of civic art is to “reinforce and communicate the layers of meaning that have accumulated within a particular city…”5 Making civic art is about two things: 1) creating monuments (i.e. works of art, often in the form of statuary, or buildings) that tell the story of the city and 2) creating settings (i.e. plazas, streets, and squares) that encourage the community to live-into the story. Monuments are those pieces of public art which concretize the story of the city. They gain their distinction from other fabric buildings in two primary ways. First, by their architectural vocabulary (i.e. height, scale, the use of grand style and other architectural details, and the quality of materials). Second, by their placement in the town fabric. Town Fabrics often set monuments on focal points of the city’s street design. In this way, “town fabric employs monuments to reflect and undergird meaning for a particular locale.”6 In this case, the memorial is set on a hill, overlooking the skyline of the small city. Montgomery is now cast in the shadow of lynching-history, slavery, and other acts of racial violence. The memorial encourages the community to remember with hope, courage, persistence, and faith.

The Town Fabric concept reinforces the importance of the city-setting in increasing the community’s ability to live-into the story of their culture. It also signals the connection between the city and memory. Through their fabric, cities retain the memories of those citizens that use, engage, and enact the story-set-in-place in their city. It is then up to the community to do in remembrance.

Quote written on end-wall of The Legacy Museum just above their parking lot.

The EJI’s new public exhibits help us remember well and confirm that the only way to “transform culture” is to make new culture. Their memorial represents a counter-culture, a counter-narrative that confronts the southern story deeply entrenched in “The Cradle of the Confederacy.” In a state that still celebrates Confederate Memorial Day, Bryan Stevenson and his team are transforming their city. We couldn’t help but see resonance between their work and the story at the core of all just culture-making. Long ago, a dark-skinned King hung from a tree on a hill outside the city of Jerusalem, lynched despite his innocence. The story of his death and resurrection ushered in the possibility of a new city where justice and peace are realized. While they may not intend it, the EJI’s memorial points back to this King and forward to His city.

Footnotes

Victor Luckerson, “‘Drenched in Blackness’: Pain and Truth in Montgomery’s Lynching Memorial,” The Ringer, April 30, 2018, https://www.theringer.com/2018/4/30/17300786/montgomery-lynching-memorial-equal-justice-initiative-bryan-stevenson.

Luckerson.

Luckerson.

I am indebted to Eric Jacobsen for my understanding of town fabric (Eric O. Jacobsen, The Space Between: A Christian Engagement with the Built Environment, ed. Robert Johnston and William Dyrness (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012).

Jacobsen, The Space Between, 16. In particular, Jacobsen notes that civic art was the task of inculcating values in public settings. Civic art as a discipline is no longer practiced, but the work of city planners today still considers the use of civic art in organically shaping the city.

Jacobsen.

Sections of this article are from Seeking Zion: The Gospel and The City We Make, written by Emanuel (Ricky) Padilla. 2017.