This fall we are featuring three pieces by student writers who are engaging theologically as bi-cultural leaders. We are thrilled to give platform to these up and coming voices who will surely shape the trajectory of the mestizo church. -The Editors

Before I began my PhD program, I had the privilege to live, work, and worship in East Chicago, Indiana, a small city near the Illinois-Indiana border whose racial demographics are almost evenly divided between African American and Latinx communities. I taught seventh-grade English Language Arts at the local middle school for five years while serving as Christian Education Director at my local Latinx Pentecostal church. The main responsibilities of this role included weekly Sunday School programming as well as annual events like Vacation Bible School. However, I became disillusioned by the disconnect between the church and the surrounding community. I would see my students playing outside on the same street as the church and wanted to invite them to participate in church gatherings, but I doubted if the experience would be life-giving. I wanted to keep my students safe as they were already experiencing the violence embedded in the US public school system. Rather than supporting them in their learning and development, school was a space where they were othered; their voices missing from the curriculum; their appearance and behavior surveilled, scrutinized, and ultimately admonished. And the church was not exempt from perpetuating those same logics that criminalize children of color for simply existing. Noticing this overlap, I yearn for a world otherwise, one with an abolitionist orientation where all members of the Beloved Community are allowed to be imperfect but held accountable, joyful, and above all, safe. My hope is that the Church, as an integral community partner, would lead this initiative. If we start here, we can impact other institutions and spaces.

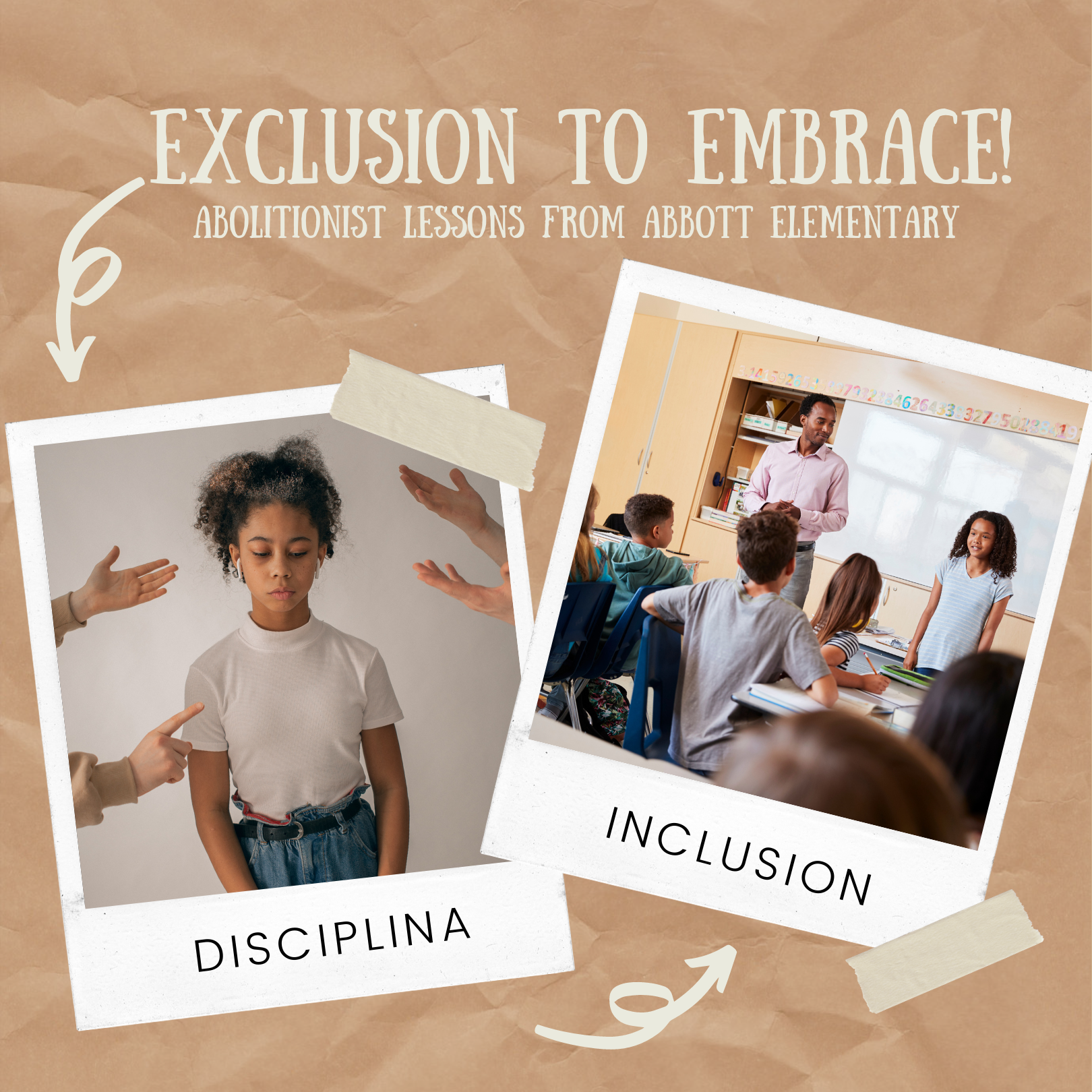

The otherwise world where children of color are not criminalized for appearance or background depends on a shift from shame and punishment as responses to harm, to an abolitionist orientation. The ways in which we interact and respond to each other in various environments, including school, church, home, and the larger community reveal our values and commitments.

Are we committed to relationship and story or shame and punishment? An abolitionist orientation embraces love, deep community, and accountability. The shift toward relationship is key considering the disproportionate punitive measures experienced by students of color, particularly Black girls, in urban public schools. According to Walker, Green, and Shapiro, “A New York Times analysis of the most recent discipline data from the Education Department found that Black girls are over five times more likely than white girls to be suspended at least once from school, seven times more likely to receive multiple out-of-school suspensions than white girls and three times more likely to receive referrals to law enforcement.” Monique Morris explores this issue more in-depth in her book and subsequent documentary, Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools. In my time as a middle school teacher, I remember seeing students walk through metal detectors and have their bookbags inspected before they could even receive breakfast. If they were considered disruptive or disrespectful, they could receive a lunch detention where they had to eat silently in a room separated from their peers. Multiple incidents often led to in- or out-of-school-suspension where students would be isolated at home for anywhere from 1-5 days.

In many local churches, including the one where I served, the practice of disciplina also indicates an orientation towards punishment via exclusion. When an action was committed that was deemed unfit by the pastor because it went against church norms and/or Christian values, the person on disciplina would be excluded from participation in church activities. Sometimes this also included revoking their titles and positions from leadership. The extent of the isolation during a person’s disciplina was ultimately at the discretion of the pastor, much like how a school administrator determines how long a student is suspended. In both church and school, isolating a community member does more harm than good. Instead, an abolitionist orientation invites accountability through deep community. How are we working together as one body to hold each other accountable while still showing love?

Abbot Elementary is an unexpected example of how to apply an abolitionist mindset to a space tainted by dynamics of punishment and exclusion. For fans of television sitcoms, Abbott Elementary is a refreshing addition to the genre. Following the hilarious and, at times, heartbreaking happenings of an urban public school in Philadelphia, the series deals with issues such as underfunding, integrating technology, surveillance, and building community among students and staff in a “mockumentary” style. As a former public school teacher and an emerging Christian education scholar, the show hits home.

Donate Today

Articles like this one are made possible by the support of readers like you. Donate today and help us continue to produce resources for the mestizo church.

In the fifth episode of the first season, a student named Courtney is transferred to main character Janine’s (Quinta Brunson) class. Courtney quickly commands control of the classroom by having the other students call her by the teacher’s name and changing the words to the Pledge of Allegiance. In many traditional classrooms, these kinds of behaviors would have resulted in Courtney being disciplined with detention or suspension for being disrespectful and disruptive. After reading Courtney’s file, Janine realizes Courtney is extremely intelligent and acting out of boredom, so Janine disregards the disciplinary advice from a senior colleague who previously had Courtney as a student. Instead, she works with the school admin and the other teachers to find a better placement for Courtney. While Courtney was doing things that were disruptive to the class, the onus was placed on the teachers to figure out what would be the best learning environment for her and her classmates. This gives an example of turning towards accountability rather than exclusionary punishment, and it was not possible until the teachers took the time to honor the full story of their student.

An abolitionist orientation toward accountability and story aligns with the vision of Beloved Community reflected in the teachings of Jesus.

He sat down, called the twelve, and said to them, “Whoever wants to be first must be last of all and servant of all.” Then he took a little child and put it among them, and taking it in his arms he said to them, “Whoever welcomes one such child in my name welcomes me, and whoever welcomes me welcomes not me but the one who sent me.”

–Mark 9:35–37 (NRSV)

Jesus is inviting the disciples into a similar shift away from the competitive, cutthroat way of life and into an abolitionist orientation towards accountability and deep community where the most vulnerable are protected and prioritized. In a world of exclusions, I pray that our schools, churches, and other community institutions would be spaces where children of color experience embrace. Bettina Love explains it this way, writing:

The practice of abolitionist teaching [is] rooted in the internal desire we all have for freedom, joy, restorative justice (restoring humanity, not just rules), and to matter to ourselves, our community, our family, and our country with the profound understanding that we must ‘demand the impossible’ by refusing injustice and the disposability of dark children. (Love, 7)

An abolitionist orientation welcomes children of color to be their full selves without fear of punishment and rejection. All members of the mestiza Church, educators and non-educators alike, can participate in the co-creation of this abolitionist world, as directed by the Teacher Himself, who calls all into abundant life.

About Adriana Rivera

Adriana (Dri) Rivera, a lifelong learner of Puerto Rican descent, is a former 7th grade English teacher and lay leader in Christian Education and youth ministry from Northwest Indiana. She studied Secondary English Education at Indiana University Bloomington before earning her MDiv at McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago. She is currently pursuing a PhD in Christian Education and Congregational Studies at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Evanston, IL with concentrations in emancipatory pedagogies and decolonial theologies. By practicing an abolitionist pedagogy, she imagines a world otherwise where all members of the Beloved Community can experience abundant life, sin vergüenza.

Footnotes

This article is an adaptation of an unpublished paper for a course at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary

Articles like this one are made possible by the support of readers like you. Donate today and help us continue to produce resources for the mestizo church.