Chicago will be heaven on earth, the garden-city promised at the end of the Bible. That was literally what Daniel Burnham believed of Chicago’s future if its citizens faithfully carried out his city plan (pub. in 1909). According to Burnham, the people of Chicago possess a spirit that reflects “the constant, steady determination to bring about the very best conditions of city life for all the people.”[1] This spirit is not merely civic pride; it is a kind of power that controls the great work of Chicago as far back as the World’s Fair of 1893. In the eighth chapter of his plan, Burnham recounts the many projects accomplished by Chicagoans and concludes “the public… has the power to put the plan into effect if it shall determine to do so.”[2] If only it were so simple.

If only the city of heaven could be planned and built by will and determination. Would not all well-planned cities be heavenly if this were the case? The presumption of this plan is still astounding to me. In truth, Burnham’s plan is remarkable. It is a vision for a future city so thorough that it continues to capture the imagination of Chicagoans today. But it is not the only time a city claimed to be in the present, or future, a vision for the ideal human home, so as the first anniversary of the release of Black Panther arrives, its time to reflect on the vision of Wakanda’s Birnin Zana, the Golden City.

The World Behind the Golden City

In preparation for the film adaptation of the Marvel comic, production designer Hannah Beachler spent 10 months writing a 500-page plan for the city.[3] Despite the futuristic technologies of the Golden City, Beachler said her goal was to focus on the people.[4] This is apparent in the brief glimpses of the city’s market. Birnin Zana is a pedestrian-friendly city. It is built for walkability, and it relies on maglev-trains and highly advanced trotros (i.e. minibuses) for longer commutes.

// Laura Bliss, “The Maglev Train from ‘Black Panther’ Is the Transit We Deserve,” CityLab // Marvel Studios

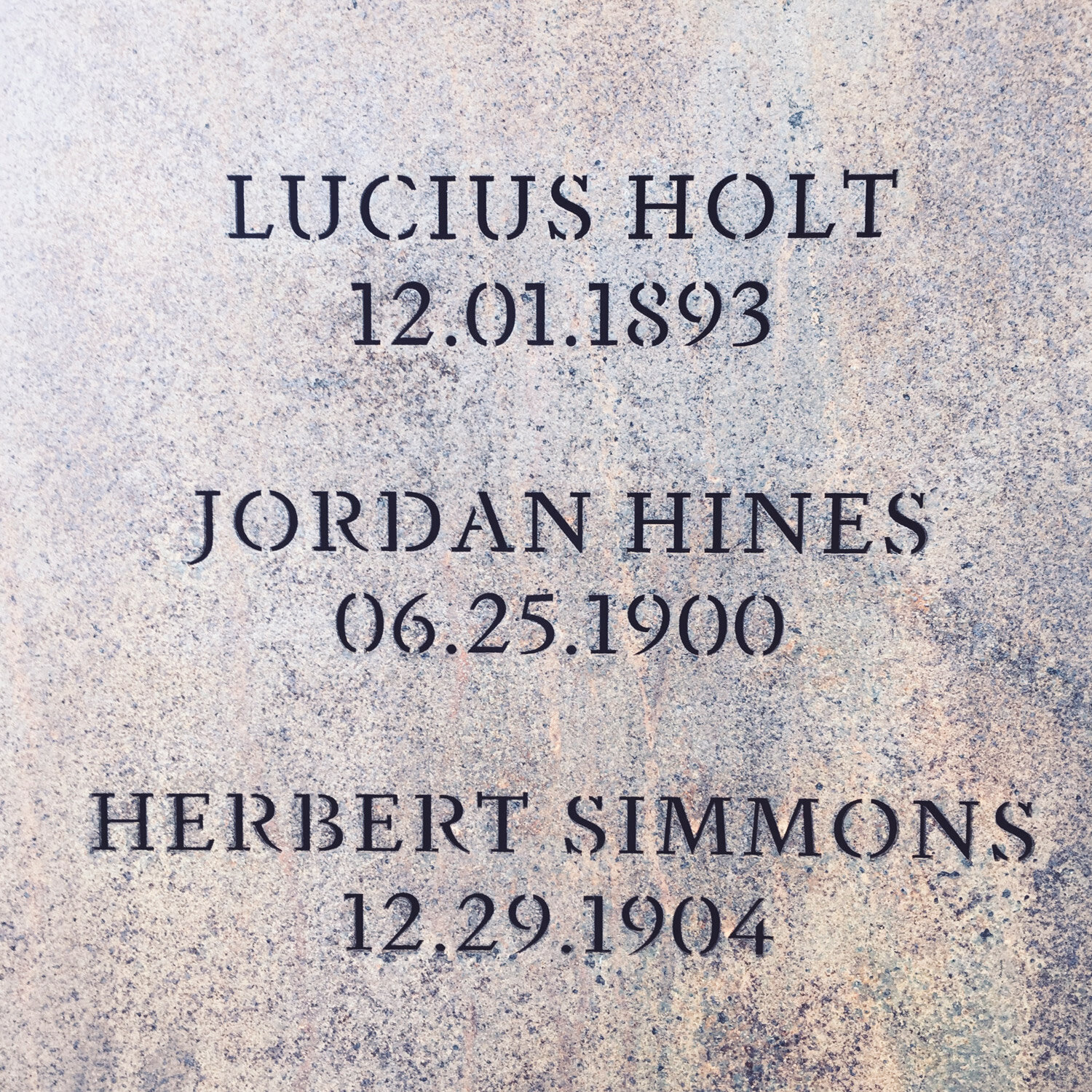

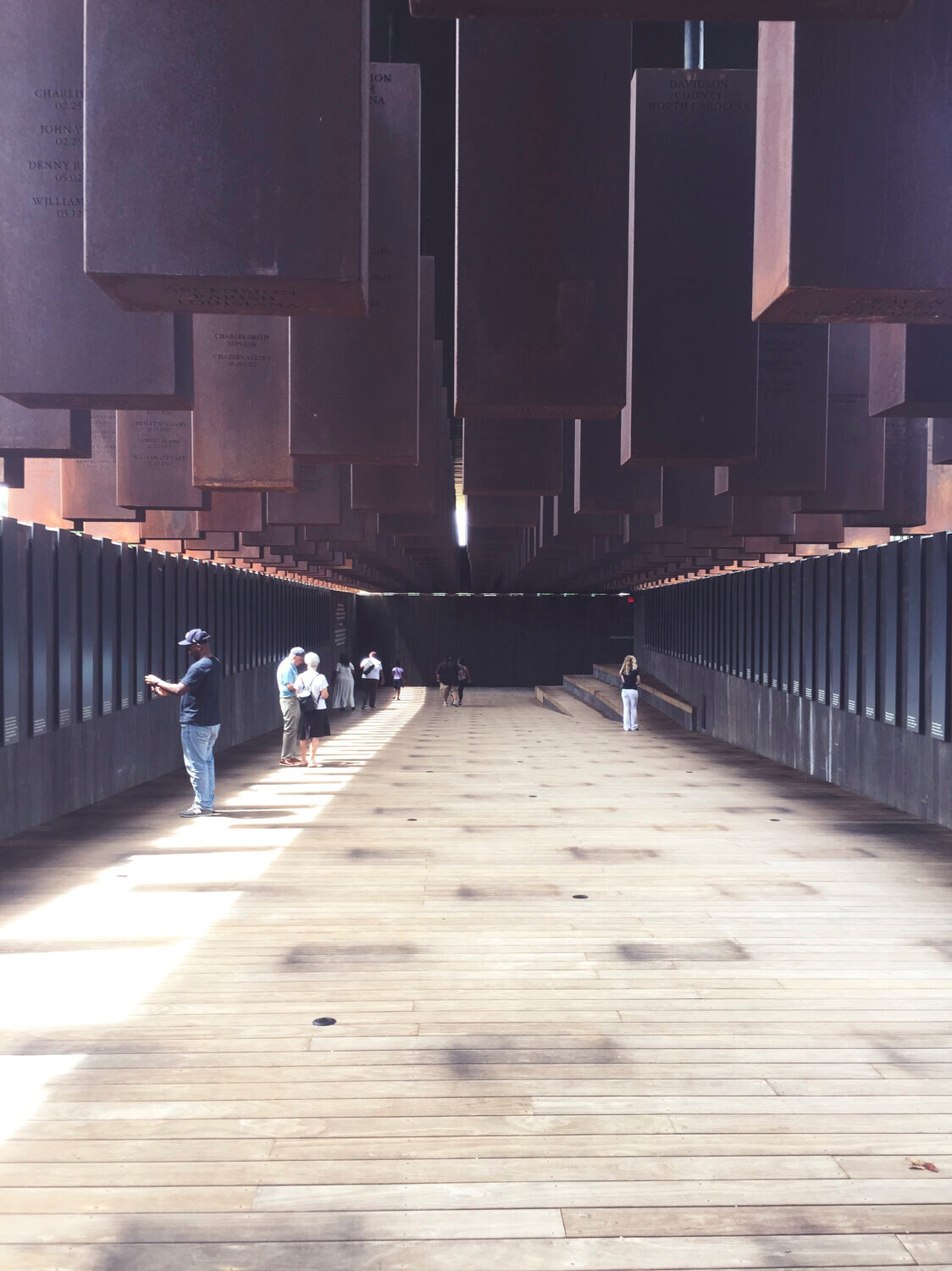

In addition to detailed infrastructure design, the plan included a history of Wakanda and its capital city and names for every building. At the heart of the city’s design, Beachler put a building she named, The Records Hall.[1] She chose to highlight this building “Because [Wakanda residents] know everything about their past”—a privilege that real-world African Americans don’t have— “and [that] will never go away again in this city.” She continues saying, “I felt that way because I never knew my history. I didn’t know my ancestry, I didn’t know how far back it went …That was truly the most important thing to me. I don’t have that, but I could give it here in this fantastical world.”[5]

Given the design choice, remembering well is built in as an important value for the city. The choice to make memories the centerpiece of Wakanda’s capital reflects profoundly on the real-world lack of history for many blacks and Hispanics here in the US. It also indicates the wisdom in Beachler’s design. All cities are built to communicate a story (see previous article). The buildings, streets, and plazas work as monuments that support the community by reaffirming their values, virtues, rules, and dreams. Burnham did something similar. In the seventh chapter of his plan, he presents the “Heart of Chicago” and the heart of his beliefs in the form of a building he called the Civic Center (see picture below).

// Burnham and Bennett, Plan of Chicago, iv.

This building would be the symbol that would sit both literally and metaphorically at the center of his proposed city. Like the Duomo of Florence, the Forum of Rome, or the Acropolis of Athens, the Civic Center would embody the civic life of Chicago. It would combine the functions of these historical icons to sustain and nurture the intellectual, business, social, and spiritual life of the citizen. This symbol represents all that Burnham idealized and is presented as “the keystone” of the city,"[6] yet despite a few attempts at a building like this one, Chicago has no Civic Center. The Record Halls and Civic Center both remain a dream.

The World of the Golden City

Like El Dorado, Golden City is hidden from the world, kept like a precious treasure. It is a technologically advanced, prosperous, and healthy Chocolate City. Brentin Mock goes so far as to call it “the apotheosis of a Chocolate City,”[7] but this near-divine refuge of black culture is hidden from the real world where colonization ravaged Africa. Mock makes an interesting observation regarding Wakanda’s isolation. He writes,

What also keeps Wakanda secure is the fact that it is completely sovereign, accountable only to its own leaders, and it trades and does business exclusively with its own people. Wakanda is not eager to take in foreigners from other countries.

That kind of protectionism should not be conflated with the extreme nativism seen today from the Trump camp. While Wakanda is a fictional place, the story is situated in the real world of the audience. And so, Wakanda’s closed borders are a response to the colonialism and white supremacism that plundered and destroyed the wealth and abundance of natural resources found throughout the rest of the continent of Africa. Wakanda is also aware of the enslavement and terrorization of Africans in the Americas. Its foreign policy is formulated around avoiding similar fates.

This reasoning highlights the tension of film. Should the Golden City be kept a secret, or should its resources be shared with the outside world? Should the privileged blacks of Wakanda be committed to supporting the African diaspora? What about the colonizing nations that oppress blacks; should Wakanda help them as well? T’Challa addresses these questions at the end of the film:

Taking steps toward applying his new foreign policy, T’Challa purchases land in Oakland, California to build his first international outreach center. I see some irony in the choice of an American city as the first new compound for Wakandan missionaries. If Wakanda is meant to be a foil of the US, their approach in the conclusion fails to show any contrast. It resembles too closely the same posture taken by US missionaries and emissaries. Today, there are still mission schools and education centers in Central American countries that are essentially marketing an American ideal, promoting American exceptionalism. Still, there is something deeply human and empathetic of T’Challa’s desire to make things in Oakland as they are in the Golden City.

The World in front of the Golden City

Urbanists are fascinated with exploring Birnin Zana. They, along with fans and scholars, want more information on the design features. Some have gone on to imagine the missing details, using #InWakanda to share their ideas. The interest is so great, that curriculum and study guides have been developed. In this way, the Golden city spawned the kind of stimulation to society’s imagination that Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago inspires. Burnham’s plan was once a textbook and required reading for eighth-grade students in the city. One such student and later mayor of the city, Richard J. Daley, referred to the plan as his favorite book, and he invoked it as he proposed his urban redevelopment plans in the late 1950s.[8] Recently, the Chicago Architecture Foundation republished the plan as a graphic novel. The popularity AND promotion of both these imaginary cities suggests something about our desire for the ideal urban home.

// Marvel Studios

Chicago, the Golden City, and Zion

Both cities studied here were planned as heavenly visions for a society that is whole, beautiful, and good. In this regard, both plans are derivative. The ancient text of the Bible promises a city built by God as the final, ideal home for humanity. The ideal or blueprint for this city is called Zion. The word Zion is used a total of 163 times in Scripture. Of those occurrences, the greatest concentration is found in the Psalms and the book of Isaiah.[9] In both books, the word takes the form of an ideal. In other words, Zion represents either the standard that Jerusalem – Israel’s capital – fails to embody or a vision of what the city is becoming. All cities that are good, beautiful, and conducive to human flourishing derive these features from this archetype. But there’s a second archetype in Scripture that explains why Zion will have to be built by God and could never be built by humanity. This archetype is called Babylon.

As I wrote in a previous article, Babylon is an ancient city that sustained its power by developing parasitic systems that drew from the resources of other lands and cities. Babylon was governed by libido dominandi (the lust for mastery). The conflict between Erik Killmonger and T’Challa is rooted in the correct accusation that Wakanda lived as a selfish country. They mastered their resources by hoarding them. When T’Challa confesses the wrongheaded approach of his ancestors, he chooses instead to travel to Oakland “essentially offering the salvific words of Starchild to Africa’s lost children: “You have overcome, for I am here.”[10] Even this derivative promise points forward to the only city and only king who will establish a kingdom without death or pain. Until then, we pray for life to be on earth as it is in the true Wakanda.

Footnotes

[1] Burnham and Bennett, Plan of Chicago, 8

[2] Ibid., 119

[3] Nicole Flatow, “Why We Loved Wakanda’s Golden City So Much,” CityLab, accessed February 14, 2019, https://www.citylab.com/life/2018/11/black-panther-wakanda-golden-city-hannah-beachler-interview/574420/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Burnham and Bennett, Plan of Chicago, 117.

[7] Brentin Mock, “How Wakanda Handles the Dilemma of Saving the Chocolate City,” CityLab, accessed February 14, 2019, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2018/02/wakanda-the-chocolatest-city/553259/.

[8] Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor, American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley - His Battle for Chicago and the Nation, 1 Reprint edition (Boston: Back Bay Books, 2001), 216.

[9] The word is used 40 times in the Psalter and 47 times in Isaiah.

[10] Lawrence Brown, “The Interpretive Matrix of Wakanda (Deeper Still the Mothership Connection),” Medium (blog), February 18, 2018, https://medium.com/@BmoreDoc/the-interpretive-matrix-of-wakanda-deeper-still-the-mothership-connection-a0b01368007a.