This article is from the forthcoming Moody Center magazine, set to publish spring 2022. To learn more about the magazine and Moody Center, subscribe to their newsletter.

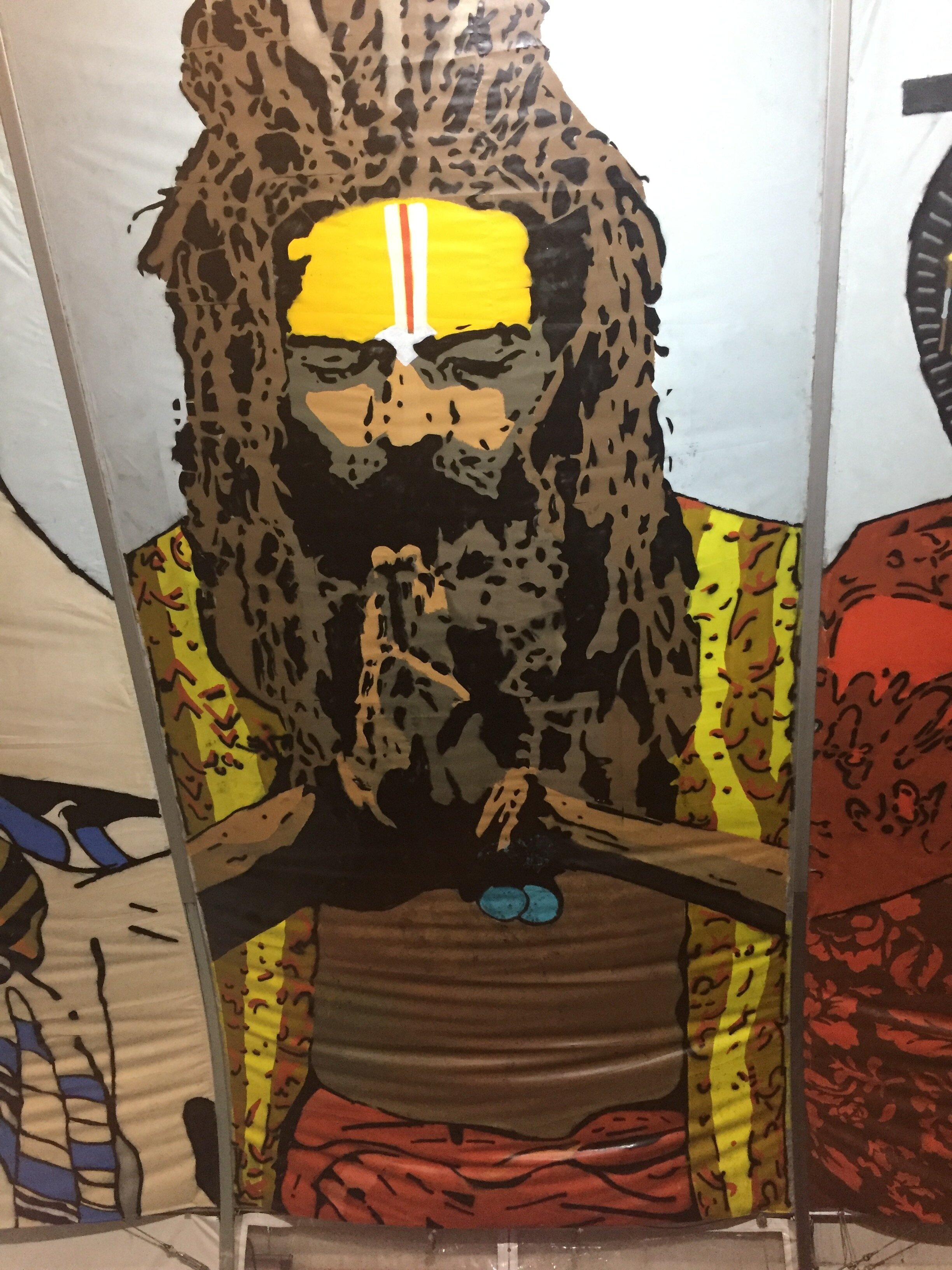

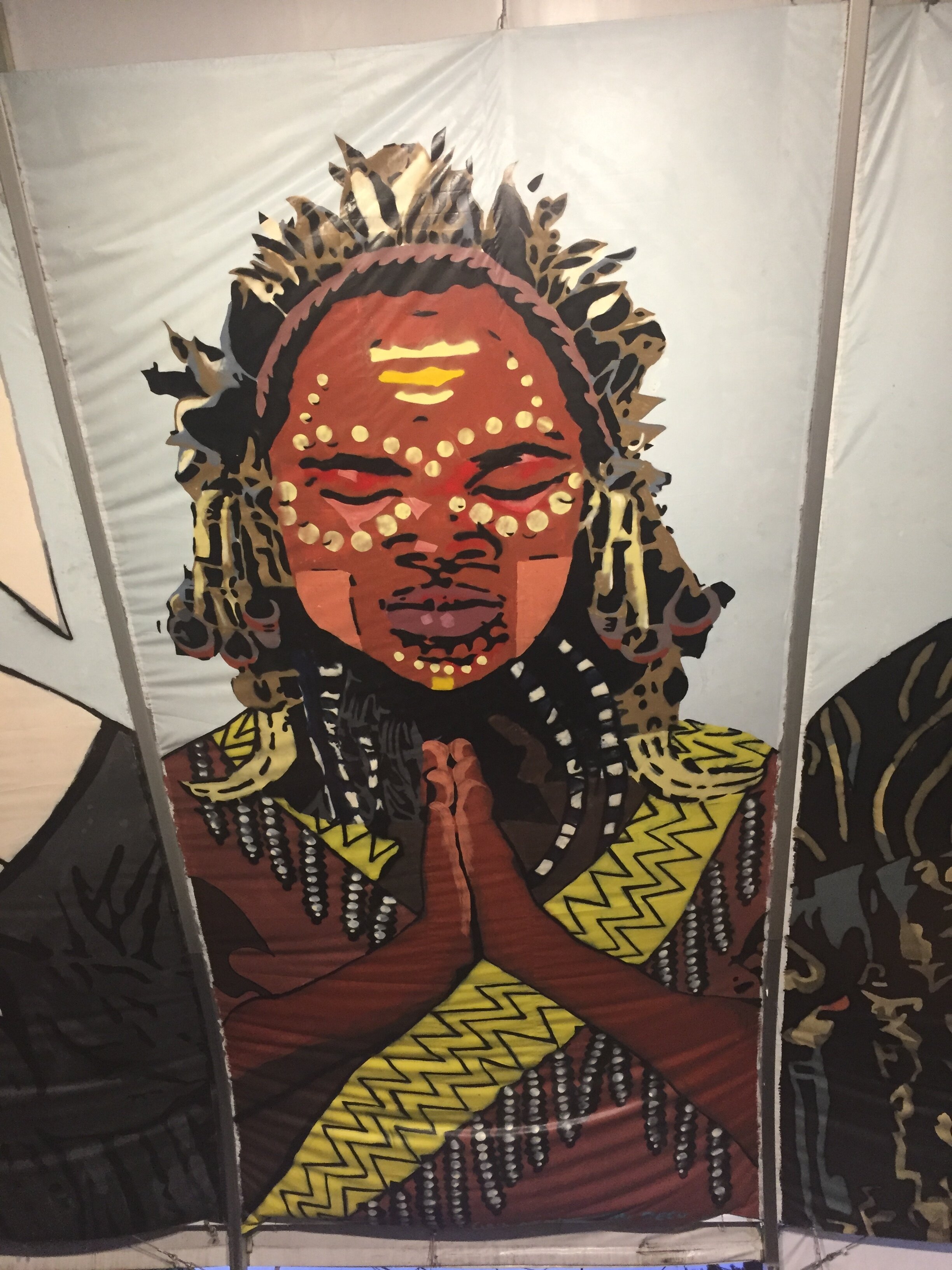

One side of my family originates from the Philippines. The other side originates from the rugged desert regions of the Southwest, the borderlands. Water buffalo, rice terraces staggered across hills, the dialects of Cebuano and Tagalog, jungle foliage, and the city of Manila, once the Spanish empire’s trading capital of Asia; the arid droughts of Texas, the linguistic conflict of Spanish and English, living between and across a not-yet militarized border, and a midday sun ascending into the Southwest skies – these are the worlds my family came from, the worlds they carry in their bodies, and the worlds that touch upon my own. But they are different from my world. I am familiar with Chicagoland: freshly mown lawn, quick and slang-filled English, single-family homes, coffee shops, super stores, the aroma of asphalt on summer days, and neighborhoods largely segregated by race and class.

I inhabit what literary theorist Homi Bhabha describes as a “hybrid” space, a metaphor meant to signify how the history of European colonial expansion and an increasingly interconnected global economy have brought once separate worlds into proximity. In my family, the trading routes of merchant marines brought my father to the docks of Texas, where he then took a flight to Chicago in search of work. There, he met my mother, whose family moved from Texas to Missouri and finally to Illinois for farm work. Their marriage gave birth to not only me and my brothers, but to a hybridity in our family life: waking up to my mother and grandmother speaking Spanish but being unable to understand them, eating eggs and chorizo for breakfast, eating chicken adobo for dinner, hearing my parents argue over whether home was in the Philippines or home was here in Chicagoland, and living within largely white suburban communities that were indifferent or hostile to the hybridity in their midst.

Being raised in the church, I have tried to take seriously that God — who journeyed with Israel and is revealed in Jesus of Nazareth — is somehow present in everyday life. So, I have always wondered: How is God present within my “hybrid” life? Who is the God that abides in the presence of multiple communities as they struggle to survive and live amidst this hybrid context?

Biblically speaking, there is good reason to think about God’s relationship to those who are living in hybrid situations as my own. In the Hebrew Scriptures, Exodus specifically, the biblical text tells us that a “mixed crowd” journeyed alongside the Israelite community after God’s Passover and Israel’s liberation from the violence of Pharaoh. The Hebrew Bible scholar Terrence Fretheim suggests that this passage on the mixed crowd implies two things: (i) that Israel herself is mixed, “consisting of more than the descendants of the twelve sons of Jacob”; and (ii) that God’s liberation of Israel had a kind of burgeoning effect. As Fretheim writes, “the benefits of freedom have a fallout effect on all those whom [Israel] comes in contact, whether they are people of faith or not.”[1] Exodus, then, tells us that God looked directly upon the nightmare of oppression experienced not only by the Israelites, but non-Israelites as well. Seeing this nightmare, God acted for their salvation, and in one sweeping act created a new community of a liberated mixed crowd.

In the New Testament, Jesus acted in consonance with God’s liberation of the mixed crowd in Exodus. In other words, his ministry was also hybrid oriented, in the sense that Jesus’s mission to the Israelites flowed into and upon the lives of non-Israelites. This is seen in Jesus’s conversation with the Samaritan woman at the well, in his celebration of the Syrophoenician woman’s faith while dining, and in his healing of gentiles such as the Roman centurion’s son. Such actions are part of what Willie Jenning’s describes as Jesus’s “reorientation” of Israel’s “kinship network” to include non-Israelites.[2] By acting for the well-being of not just Israel, but non-Israelites as well, God opens up a fellowship between Jewish and non-Jewish peoples. This expansive kinship of Jesus is on display during Pentecost, when God’s Spirit fell upon Jesus’s disciples and enabled them to speak in the languages of other peoples. Describing this Pentecostal beginning, Jennings says that “the Spirit creates joining” through immersing the disciples in the “mother tongues” of others. And by being immersed in the language of others, the disciples take on a Spirit-filled hybridity. As Jennings suggests, they are joined to the “voice, memory, sound, body, land, and place” of others.[3] Whoever the disciples are called to be, they must now consider their faith in relationship to the cultures, languages, and histories in which they were baptized.

These brief scriptural meditations suggest that God works in the material realities of multiple peoples. So, what could this mean today that God is acting among and for the salvation and liberation of multiple peoples? I want to answer this question by turning to my family history.

My family’s migration to Chicago is connected to a painful history of US colonization. Fifteen years after the end of US colonization of the Philippines, my father was born. Economic instability from World War II, the murder of his father for petty cash, and after working some time as a merchant marine, he decided to settle stateside.[4] Growing up, my father described this resettlement as a kind of choice, the will of the individual to secure the American dream. Really, the truth is more complicated. He settled mostly because a history of colonization, war, occupation, and consequently impoverished social conditions unsettled him. My mother’s story is one of more stability, but nonetheless contains the roots of an imperially induced migratory epic. From what I’ve been able to discern between her and my grandmother, my grandparents were migrant farmers who managed to secure farming land in rural northwest Illinois. From there, they raised their children, spoke Spanish and English, and worked regularly with seasonal migrant farmers and white farm owners. How they managed to secure this land while other migrant workers continued to travel for low- paying labor could be the result of their handle of the English language, English being an access point to dominant White communities and the language they encouraged their children to learn. I am not sure. At root my parents are what journalist Juan Gonzalez describes as the “harvest of empire.”[5] They were farmers within an imperial regime whose political ambitions stretched across the Pacific and US Midwest, the result being my family’s victim to colonial domination, their struggle over their heritages, the loss of languages among my brothers and I, and continual wreckoning with what it means to be mixed.

But within this history of US empire as it touches immediately upon my family, one confronts the relevance of the good news in the Hebrew Scriptures and the Gospel. God is not indifferent to today’s regimes of violence that continue to oppress many peoples. This God was active in the liberation of a mixed crowd in Egypt, was active in the creation of a mixed crowd speaking the languages of many peoples during Pentecost, and this same God is active today in those communities who are joined together by the wide grip of the empire. In the hybrid space of my family, this God sustained my father, who farmed on land his family did not own; this God sustained my mother, a little girl who was encouraged to speak English over her Spanish.[6] The presence of a God who liberates a mixed crowd is a divine affirmation of the cultural hybridity of my family and a prophet denouncement of all claims of political, economic, and cultural domination.

About Colton Bernasol

Colton is from Plainfield Illinois, a Southwest suburb in the Chicagoland area. He is a graduate from Wheaton College with a bachelor’s degree in Philosophy and Biblical and Theological studies. Currently, he is a student at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary where he is pursuing a Masters in Theological Studies with a concentration in Theology and Ethics. He is interested in questions at the intersection of theology, race, and colonialism.

Further Reading

Homi Bhabha, The Locations of Culture.

Mariana Ortega, In-Between: Latina Feminist Phenomenology, Multiplicity, and the Self

Willie Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theologies and the Origins of Race.

Willie Jennings, Acts.

Brian Bantum, Redeeming Mulatto.

Jon Sobrino, Jesus the Liberator.

footnotes

[1] Terrance Fretheim, Exodus, 143.

[2] Willie Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race, 265.

[3] Jennings, Acts, 28-29.

[4] Erika Lee, The Making of Asian America, 175.

[5] Juan Gonzalez, Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America. Kindle Addition.

[6] Jon Sobrino, Jesus the Liberator, 84.

Articles like this one are made possible by the support of readers like you. Donate today and help us continue to produce resources for the mestizo church.