This article is part of a Learning Center course called, Reading the Bible as a Mujerista Evangelica set to release on March 8th. To learn more about WOS online courses, visit learn.worldoutspoken.com.

We have to be better readers. We have to learn how to read. And we must learn how to tell stories. To know when to raise our voice and when to lower it. When to pull the people in with a whisper, and when to increase our volume!

My professor and mentor has told me this before, and now to the countless others he has taught. His love for Charles Dickens and Don Quijote seeps into the way he reads and writes, even in his academics.[1] It makes his writing interesting to read, but only because he knows that a good reader makes a good writer. It’s the reason why I am intentional about my own reading. I regularly rotate fiction and poetry books into my repertoire. I, too, believe that a good writer learns the art by being a good reader. You communicate to others by noticing the ways that best communicate to you.

The biblical authors know this too. The Old Testament narratives have this way of drawing in the reader. These writers quickly shift from artful prose to well-developed poetry, even within the stories of the historical narratives (like Deborah’s victory song in Judges 5). These stories aren’t just dry attempts to narrate without a purpose; no, these stories are meant to convey something deeper about the condition of life and add to what we already know about God. I invite you to look at Judges 19 with me, a story so grotesque that maybe you’ve skipped it over, but a story so carefully crafted that the narrator is undeniably attempting to communicate something to the readers on the other side of the page.

(Trigger warning: Rape, domestic violence, and murder. Please feel free to skip over this article.)

Judges 19[2]

In those days, when there was no king in Israel, a certain Levite, residing in the remote parts of the hill country of Ephraim, took to himself a concubine from Bethlehem in Judah. But his concubine became angry with him, and she went away from him to her father’s house at Bethlehem in Judah, and was there some four months. Then her husband set out after her, to speak tenderly to her and bring her back. He had with him his servant and a couple of donkeys. When he reached her father’s house, the girl’s father saw him and came with joy to meet him. His father-in-law, the girl’s father, made him stay, and he remained with him three days; so they ate and drank, and he stayed there.

“In those days, when there was no king in Israel…” Already the narrator sets the scene for us. Knowing the period of Judges as a time where “everyone did what was right in their own eyes” (Judg 17:6), this statement already stirs up fear for the reader. What will happen in this narrative, during a dark time of chaos and free reign?

We read that a concubine becomes angry at her Levite husband. In her anger, she decides to set out to her father’s house for a long four months. What I find interesting about this story is not what it says, but what it doesn’t say. As a Levite, this man had a higher status and honored place in society.[3] The concubine, who in contrast has a lower status in the ancient Near Eastern world as legal property of her master, does not speak. We have no clue as to why she became angry. We have no clue if her father welcomed her with open arms, but we do know that he opened his arms to his son-in-law. The narrative states the Levite’s intent to “speak tenderly” to his concubine, almost in an attempt to see him in a positive light, but then the reader begins to wonder: Why did it take four months for him to come find her? And the story states that he stayed to eat and drink, but there is no mention of the Levite actually speaking to the concubine—the very reason he came to his father-in-law’s home. In actuality, it stirs up even more uncertainty. Pay attention to how your body feels, to what remains unsaid, and to how your attitude toward the Levite shifts.[4]

On the fourth day they got up early in the morning, and he prepared to go; but the girl’s father said to his son-in-law, “Fortify yourself with a bit of food, and after that you may go.” So the two men sat and ate and drank together; and the girl’s father said to the man, “Why not spend the night and enjoy yourself?” When the man got up to go, his father-in-law kept urging him until he spent the night there again. On the fifth day he got up early in the morning to leave; and the girl’s father said, “Fortify yourself.” So they lingered until the day declined, and the two of them ate and drank. When the man with his concubine and his servant got up to leave, his father-in-law, the girl’s father, said to him, “Look, the day has worn on until it is almost evening. Spend the night. See, the day has drawn to a close. Spend the night here and enjoy yourself. Tomorrow you can get up early in the morning for your journey, and go home.” But the man would not spend the night; he got up and departed, and arrived opposite Jebus (that is, Jerusalem).

He had with him a couple of saddled donkeys, and his concubine was with him. When they were near Jebus, the day was far spent, and the servant said to his master, “Come now, let us turn aside to this city of the Jebusites, and spend the night in it.” But his master said to him, “We will not turn aside into a city of foreigners, who do not belong to the people of Israel; but we will continue on to Gibeah.” Then he said to his servant, “Come, let us try to reach one of these places, and spend the night at Gibeah or at Ramah.” So they passed on and went their way; and the sun went down on them near Gibeah, which belongs to Benjamin. They turned aside there, to go in and spend the night at Gibeah.

Here the narrator drops another hint. We know now that the Levite is traveling not only with his concubine, but with one of his servants. His title has now been changed to “his master,” almost as if the narrator is detaching the Levite from the concubine and shifting focus onto the servant. His servant makes a suggestion: to spend the night in a city of foreigners. The master says, “No thank you!” He refuses to be part of a community that does “not belong to the people of Israel.” We remember too that his association as a Levite meant that in theory, he practiced the law of the LORD. However, the reader wonders if his disdain toward foreigners disregards a law that states to love the foreigner—not tolerate, but love (Lev 19:34). He dismisses his servant’s suggestion and does what is right in his own eyes.

He went in and sat down in the open square of the city, but no one took them in to spend the night. Then at evening there was an old man coming from his work in the field. The man was from the hill country of Ephraim, and he was residing in Gibeah. (The people of the place were Benjaminites.) When the old man looked up and saw the wayfarer in the open square of the city, he said, “Where are you going and where do you come from?” He answered him, “We are passing from Bethlehem in Judah to the remote parts of the hill country of Ephraim, from which I come. I went to Bethlehem in Judah; and I am going to my home. Nobody has offered to take me in. We your servants have straw and fodder for our donkeys, with bread and wine for me and the woman and the young man along with us. We need nothing more.” The old man said, “Peace be to you. I will care for all your wants; only do not spend the night in the square.” So he brought him into his house, and fed the donkeys; they washed their feet, and ate and drank.

The woman has still been largely absent up to this point. Was she not intended to be the focal point of this entire narrative, the reason the Levite man even went out in the first place, and now the reason they are traveling back? The reader begins to wonder why the narrative feels empty, and it is the lack of focus on the woman that contributes to this emptiness. The Levite even tells this man, “Nobody has offered to take me in” instead of “Nobody has offered to take us in” (italics mine).[5] The narrator continues to drop clues about the Levite man’s character and the blatant disregard for his servant and his concubine.

While they were enjoying themselves, the men of the city, a perverse lot, surrounded the house, and started pounding on the door. They said to the old man, the master of the house, “Bring out the man who came into your house, so that we may have intercourse with him.” And the man, the master of the house, went out to them and said to them, “No, my brothers, do not act so wickedly. Since this man is my guest, do not do this vile thing. Here are my virgin daughter and his concubine; let me bring them out now. Ravish them and do whatever you want to them; but against this man do not do such a vile thing.” But the men would not listen to him. So the man seized his concubine, and put her out to them. They wantonly raped her, and abused her all through the night until the morning. And as the dawn began to break, they let her go.

As morning appeared, the woman came and fell down at the door of the man’s house where her master was, until it was light. In the morning her master got up, opened the doors of the house, and when he went out to go on his way, there was his concubine lying at the door of the house, with her hands on the threshold. “Get up,” he said to her, “we are going.” But there was no answer. Then he put her on the donkey; and the man set out for his home.

Still as the story begins to close, the woman does not speak. And now, as the Levite demands her to “get up” because they should be on their way, we as readers do not know if she is alive. It confirms all of our suspicions picked up throughout the narrative—that the Levite’s character is less than exemplary.

When he had entered his house, he took a knife, and grasping his concubine he cut her into twelve pieces, limb by limb, and sent her throughout all the territory of Israel. Then he commanded the men whom he sent, saying, “Thus shall you say to all the Israelites, ‘Has such a thing ever happened since the day that the Israelites came up from the land of Egypt until this day? Consider it, take counsel, and speak out.’”

The story still never tells you if the concubine was alive or not. Her silence lingers until the very end. Instead, the Levite man takes control of the situation by gruesomely dismembering her. And, instead of taking responsibility for his actions and their outcome, he has the audacity to point fingers at the Israelites! As everyone did what was right in their own eyes, he blamed the dark and preventable death of his concubine on the state of society. Maybe if people spoke out, then the men wouldn’t have come to rape them, and then perhaps this “thing” would not have “ever happened.” We know that the Levite man’s complacency in the systemic sin found in the period of Judges contributes to this abomination just as much as the wickedness of the men did.

Being on the other side of the story, even more questions arise. Did the concubine have good reason to leave in the first place, considering the outcome of her story? Would this violence have been averted if the servant’s suggestion was followed, or was this bound to happen due to the Levite’s less-than-holy character? And finally, what is the narrator trying to convey with a story so brutal, one that begins with a woman afforded no agency or words and ends with her rape and death?

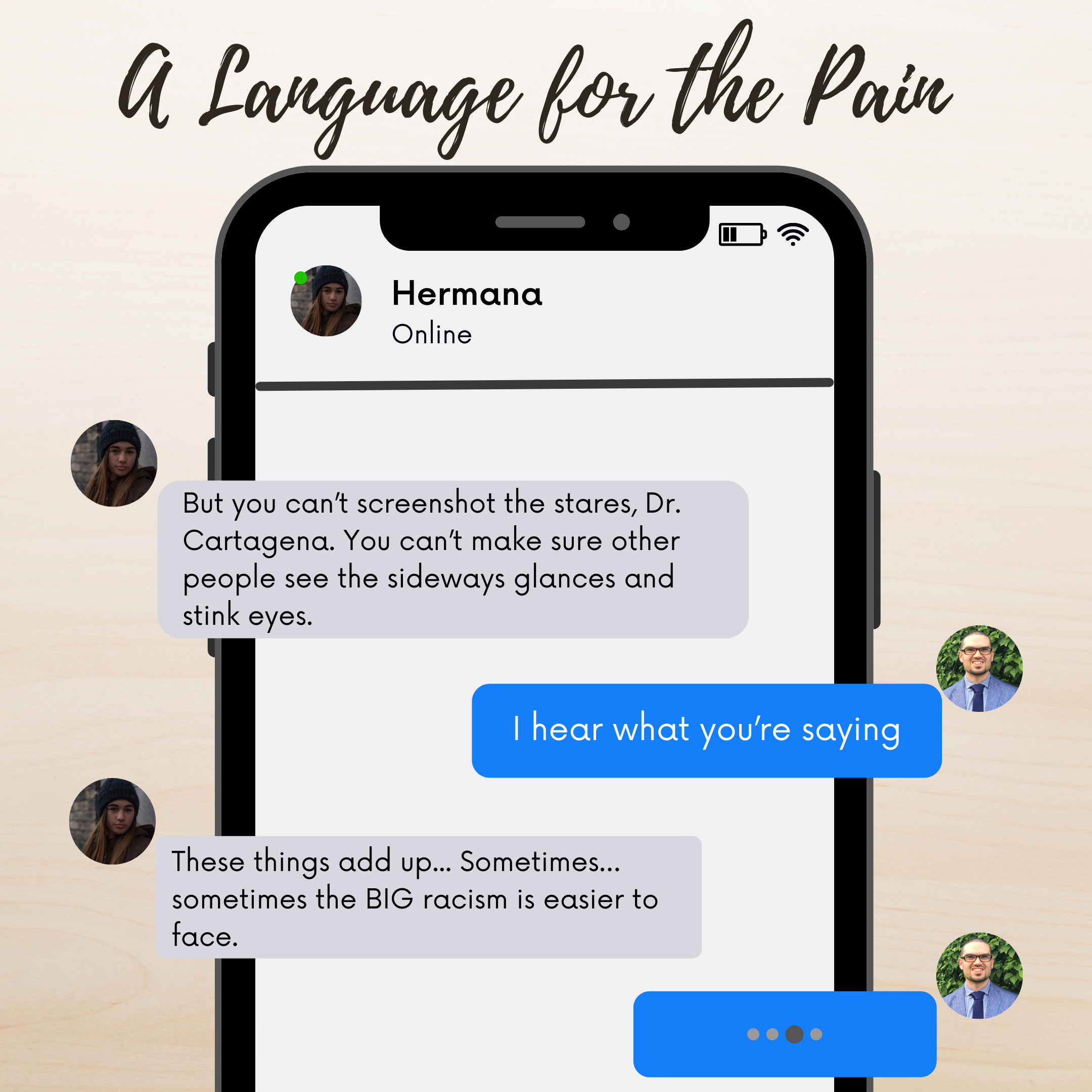

When we read stories like this, our minds always shift to ask how something like this could be included in our Old Testament Scriptures. It is important to acknowledge the implications of such a text. First, like many of the Old Testament stories, this story is not meant to be prescriptive but descriptive. After careful analysis, readers see that the narrator’s craftsmanship of the story shows that they were never on the side of the Levite. Thus, a theological, real-life lesson can be extracted. Second, the Old Testament does not shy away from acknowledging the hurts of this world. Although we hate encountering stories like this, we know that our fallen world is scattered with situations that read just like this one. And for those who have experienced these situations, it gives us words that describe something that we may not have even processed ourselves.

As Phylllis Trible puts it, this story “depicts the horrors of male power, brutality, and triumphalism; of female helplessness, abuse, and annihilation.”[6] The moment the Levite decided to mistreat his concubine, everything went downhill. If you continue on to read Judges 20, you see that things continue to spiral downward as an effect of the woman’s death. The flourishing of women, or lack thereof, is directly correlated to the health of this society. This society is indeed in need of a savior. The mistreatment of the oppressed and marginalized, specifically women here, can only result in a society that perpetuates even more oppression and marginalization.

About Michelle Navarrete

My passions stem from within the Old Testament, focusing on biblical themes and social ethics through an interdisciplinary approach. As a second-generation Latina who lives in between the Mexican and American cultures, my faith inevitably intersects with my culture and experiences. I use storytelling in my academics as a way to engage my audience and cultivate connection. People are part of my passion and I want my work to reflect that. Currently located within the Latino community of West Chicago, I am pursuing my master’s in Old Testament Biblical Exegesis at Wheaton College, and I intend to pursue doctoral studies after my time at Wheaton. During my time at World Outspoken, I hope that my contributions will renew faith perspectives in a way that mobilizes restoring change within communities.

Footnotes

[1] Dr. M. Daniel Caroll R. intertwines his love for narrative and storytelling, and even contextualizing from the Latina/o perspective, through the prophetic voice in his new book The Lord Roars: Recovering the Prophetic Voice for Today. Shameless plug.

[2] I invite you to read this without the verses marked, like a story. For your reference, this is the NRSV translation, and the entirety of chapter 19 of Judges.

[3] Phyllis Trible, Texts of Terror: Literary-Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives, 66.

[4] For a more comprehensive treatment of the narrator’s possible intentions, see Jacqueline E. Lapsley’s work, “A Gentle Guide: Attending to the Narrator’s Perspective in Judges 19-21.”

[5] Lapsley, 43.

[6] Trible, 65.

Articles like this one are made possible by the support of readers like you. Donate today and help us continue to produce resources for the mestizo church.