Should I stay or should I leave? Am I trapped in the barrio or is the barrio an inescapable, yet beautiful part of me from which I should not flee (or even have the desire to leave)? Should the life-taking stories of my barrio take precedence (like they do in the news) or do I privilege only the life-giving (counter) narratives that dignify my city? If I stay, am I being a bad parent, allowing my son to remain in a potentially dangerous environment where opportunity and resources are scant? If I leave, am I being a bad Christian by opting for my family’s and my own comfort and safety?

These questions invaded my mind and the noises of my barrio played a conflicting melody where love, sacrifice, injustice, and pain entwined.

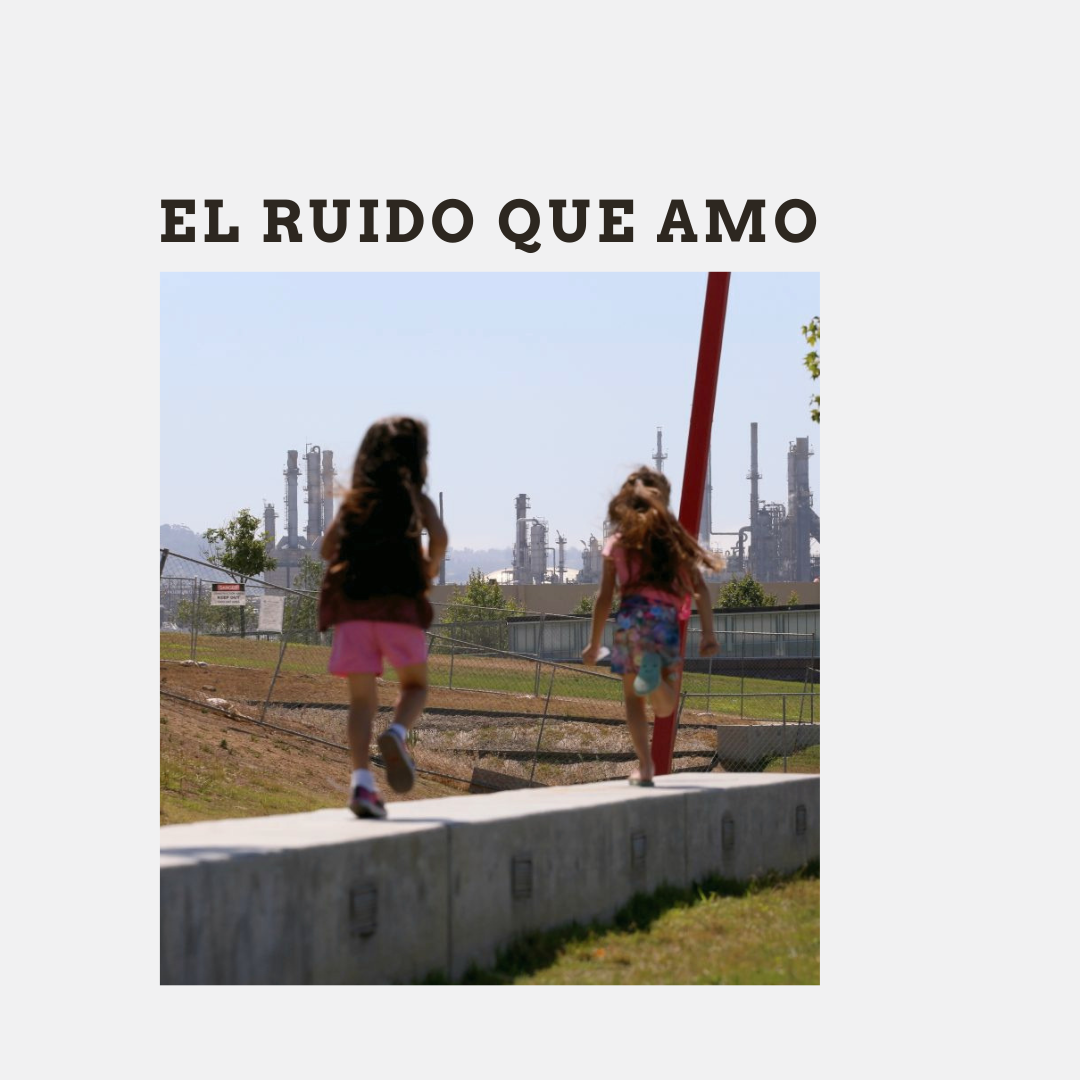

El ruido que amo (the noise that I love)

I love las cumbias, las rancheras y los boleros I hear desde mi ventana. I didn’t exactly request this music pero my neighbors’ music selection is everyone’s delight. Ok, maybe not everyone’s, but I like it. I’ll be hanging out in my back yard and suddenly la canción de Ana Gabriel que puso la vecina gets me going, and I start singing my heart out: ¿Quién como tú, que día a día puedes tenerle? It takes me back to the many road trips I took with my parents when I was a little girl. Ana Gabriel, Juan Gabriel, Los Bukis – those were my jams!

I love el ruido que mi gente makes when they’re hussling. Tamales, tamales, tamales. ¡Tamales de piña, de puerco, de pollo, tamales! I love when my son runs out yelling raspadooo when the street vendors pass by honking their horns announcing la llegada of those delicious raspados we all slurp with such gozo. I love hearing mi pueblo use their voice to try to make ends meet en el swapmeet: barato, barato, barato, pásele; ¿qué le damos, señorita, pásele a lo barato?

I love la euforia que se escucha cuando la selección mexicana scores a goooooooool!

Whoever said my people have been silenced, has not set foot in my neighborhood.

El ruido que odio (the noise that I hate)

I hate that I can distinguish the sound of fireworks from gunshots. I hate that we have to run inside the house and lock every door when we hear shots fired. I hate that every other day police sirens and the noise of helicopters drown out the sound of my favorite TV show, reminding me that I am not safe. I hate the cries of yet another grieving mother as she pleas with the public to help her find her child’s murderer.

El ruido que amo y el ruido que odio are juxtaposed mainly because “U.S. barrios have been a source of cultural resistance; they function as reterritorialized spaces where it is possible to maintain one ́s culture and to resist assimilation. At the same time, the barrios are social spaces where ethnic lower classes are segregated thus impairing their economic development and creating a subculture of violence and poverty.”[1]

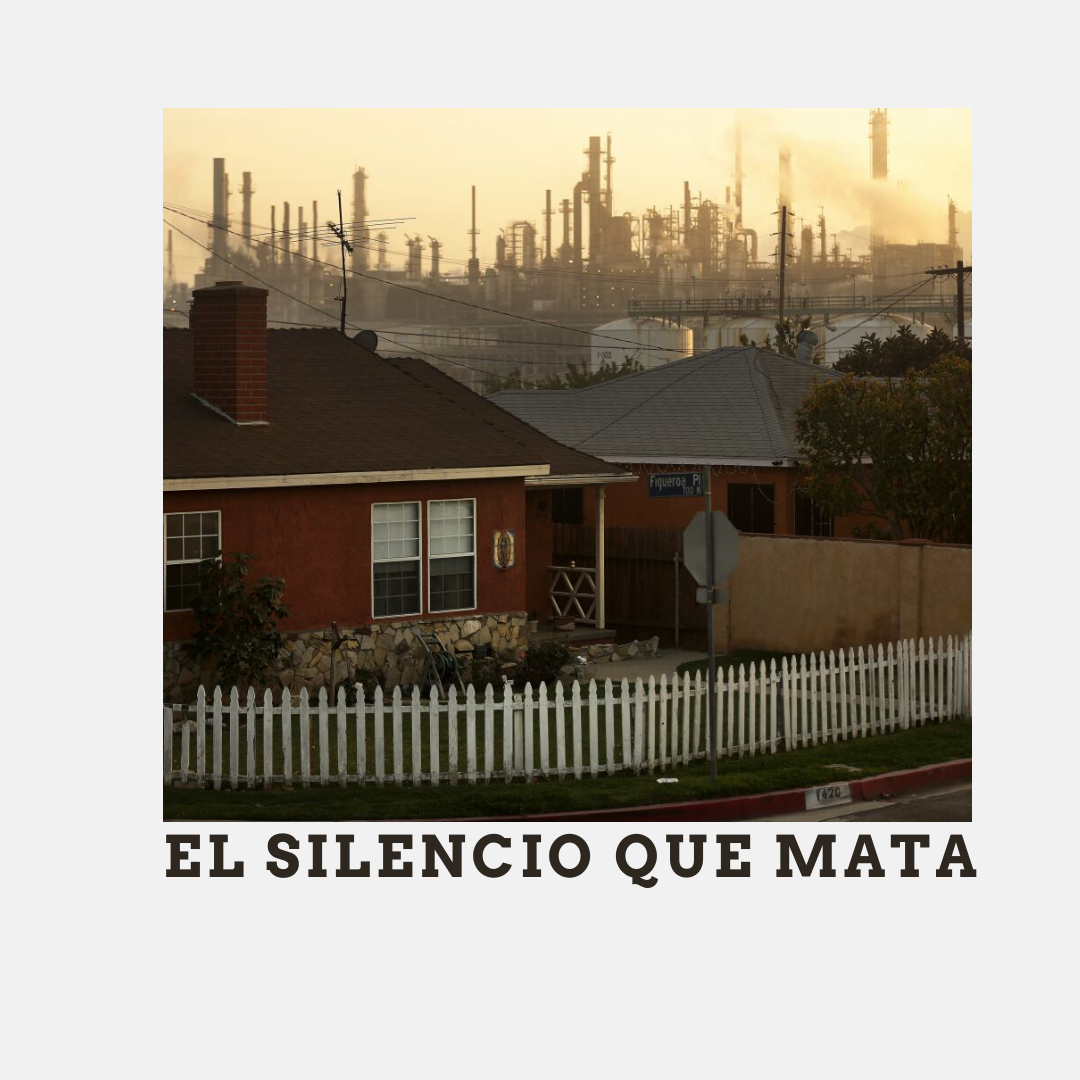

El silencio que mata (the silence that kills)

But the most murderous force in my neighborhood is silent. The culprit hides in plain sight. More than two thousand pounds of toxic chemicals are emitted in Wilmington, California every single day. My beloved city is surrounded by the largest concentration of oil refineries in the state and the third largest oil field in the contiguous U.S., and it is home to the largest port in North America (Grist 2022). Wilmington, which is 90% Latino and 40% immigrant, is a toxic wasteland; the dumping grounds of big oil corporations. The contaminants expelled daily create diseased bodies in a community where the median household income is 40% below the state’s average and where 28% of its residents are not medically insured, a number that represents three times more than the national average. The environmental hazard created by these companies also has an impact on violent crime. Several studies have found a link between violent crime and pollutant exposure: “air pollutants act as stressors, eliciting endocrine stress responses in our brains that lead to irrational decisions and violent tendencies and also disturb the physical, cognitive and emotional health of people exposed to it at high levels” (The Guardian 2022).

Wilmington, CA; they call it a “bad neighborhood” and bad neighborhoods are always bad because of the individuals that inhabit it. A “bad neighborhood” is never thought to be bad by virtue of systemic injustices that include racial and environmental inequalities. My family and I are from a “bad neighborhood,” but I don’t think we’re bad people. Jesus himself was from Galilea, a neighborhood deemed undesirable. Dr. Chao Romero asserts that if Jesus was from California, he would not come from Beverly Hills or Calabasas, but the most marginalized regions of the state, like East LA or the Central Valley.[2]

What we really mean when we say “bad neighborhood” is impoverished, and, often, Brown or Black. The “good neighborhoods” are strictly regulated. Associations determine rules about the colors in which you are allowed to paint your house, how often you’re supposed to do your lawn, and how much noise you can make. “Good neighborhoods” are wealthy, have good school districts, lower crime rates and are predominantly White. Language matters because language constructs truth. The use of “good/bad” as it refers to neighborhoods continues to strengthen the belief that the people who live there are inherently bad and completely disregards systemic issues that have created and continue to sustain the disenfranchisement of our barrios.

I understand the ways in which systemic issues have worked against my community. I love my community for the ways in which it has shaped me to be resilient, humble, and faithful. I am grateful for the ties I have formed there and the life lessons that have been imparted to me: to not judge people by what they have or where they came from. Nonetheless, there is another competing truth: I have witnessed more gun violence than the average American, I attended low-performing schools in the area and do not feel safe letting my teenage son walk alone to the store that is 100 feet away from my house. I have lived in this city for over 30 years and there is a certain level of comfort granted to me by familiarity, but as a mother, I face a conundrum: do I stay or do I leave?

Deciding to leave our barrios is more than aspiring to a bigger, nicer house with abundant parking, and plentiful green spaces. Leaving our barrios means that our children will have better educational opportunities, access to resources that improve their livelihoods, and the probability of being less exposed to violent crime. Ironically, the dilemma many of us face is similar to the one experienced by our first-generation immigrant parents with one distinction: my socioeconomic status and educational levels have significantly improved while remaining in my native community.

The Christian Community Development Association (CCDA) emphasizes a ministry of presence in which believers are active members of the communities in which they serve. It is a way of doing ministry that decentralizes white saviorism and centers the voices of community members. They invite people to be wholly present in their areas of ministry by becoming (and remaining) a neighbor. As a Christian that understands the importance of serving the socially dispossessed, am I to remain and use my social and economic capital to help my community flourish or should I leave relocating in a city where my children will be safer and have access to opportunity?

I left. It might seem like that was the easiest decision to make, but it certainly didn’t feel that way. I wrestled with this decision for quite some time, asking the Lord for guidance: “Lord, help us; ayúdanos a entender tu voluntad.” Months later, my husband and I received an answer to our prayers that gave us the certainty that we were being called out of my beloved city. In very God-like fashion, he set the pieces in motion and directed our steps.

So, should you stay or should you leave? I don’t know, and I don’t think there’s a generic right or wrong answer. God directs our paths in unique ways in different seasons of our lives (Ecclesiastes 3: 1-8). For people of color, these decisions are especially difficult as we encounter survivor’s guilt. Dr. Piorkowski explains that survivor’s guilt, or success guilt, is prevalent amongst first-generation college students from marginalized communities. We often ask ourselves – and God – questions that are filled with remorse: Why did I succeed when so many others in my neighborhood didn’t? Why am I alive when many of my classmates aren’t? Why do I have the opportunity to live in better conditions when many of my family members don’t? How is it possible that I love my barrio, but still want to leave it?

Guilt and gratefulness collide, but this guilt is crippling because it doesn’t allow me to faithfully receive God’s blessings. Instead of viewing the earth as a punishment that we must endure to buy our way into Heaven, we must understand the earth as a good place created by God (Genesis 1:18; Genesis 1:31) and our salvation as a free gift from our Lord (Ephesians 2:8; Romans 6:23). Perhaps God is indeed calling you to stay, but the decision to remain should not be guided by guilt. Conversely, if we are being led to leave, we must not do so developing a posture where we see our former neighbors as less-than, or inherently lacking, because of their socioeconomic status, and in doing so, engaging in the further dehumanization of our barrios. Remember that “You will always be Esperanza. You will always be Mango Street. You can’t erase what you know. You can’t forget who you are” (The House on Mango Street).

About Dra. Meduri Soto

As an academic from el barrio, Dra. Meduri Soto strives to engage in scholarly work that honors and gives visibility to her community. Her faith drives her passion for justice as she seeks to reveal the ways in which certain language ideologies are constructed to operate unjustly against our communities. Her work acknowledges language as a powerful tool and promotes linguistic diversity in its different manifestations. Bicultural and bilingual identities are at the center of Dra. Meduri Soto’s work. She is a Spanish professor at Biola University where she teaches second language and heritage language learners. To learn more about her work, follow her on Instagram: @la.dra.itzel

Footnotes

[1] Views of the Barrio in Chicano and Puerto Rican Narrative (Antonia Domínguez Miguela)

[2] The Brown Church: Five Centuries of Latina/o Social Justice, Theology and Identity (2020)

Articles like this one are made possible by the support of readers like you. Donate today and help us continue to produce resources for the mestizo church.