“I would like to be known as a good friend.” The words came out as I processed with my spiritual director how I felt perceived by others. I have been called intelligent, a good preacher, teacher, and even theologian (I am an amateur at best). But even if I enjoyed being on the receiving end of those compliments (I’ll spare you the not-so-positive ones), I realized the one thing I really wanted to be known for was being a good friend.

What I didn’t see at that point was that friendship is more than a nice personal trait, but that it has everything to do with the gospel, with our life of faith, and even with our theology. As it usually happens to me, a good book would enlighten me.

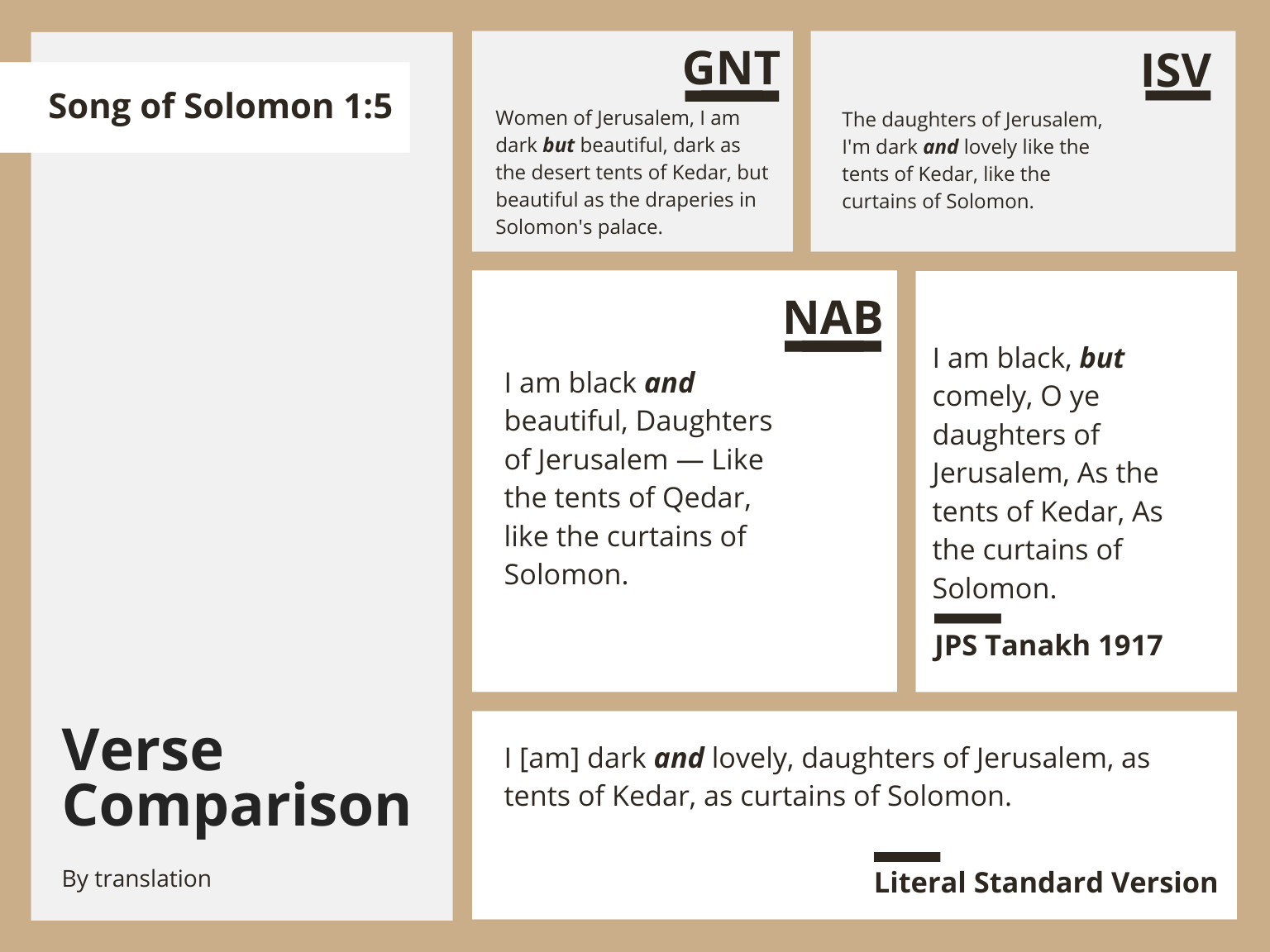

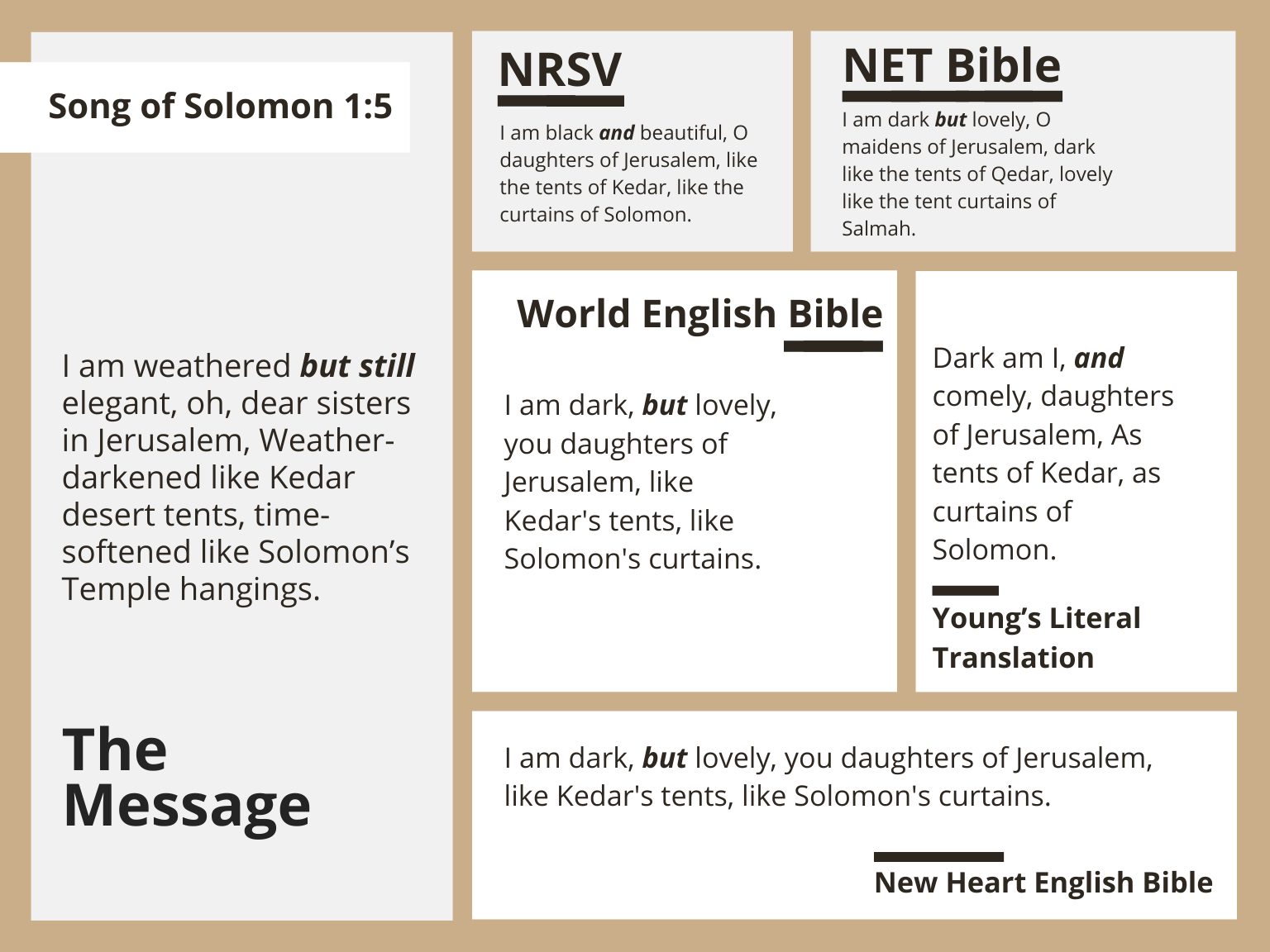

In La porfía de la resurrección (2008), Dra. Nancy Bedford writes several important corrections to ministry and theology: the importance of reading the Bible through the lens of women (both in its stories and the rest of history), the dangers of a toxic Christology (especially toward women), and the place of disloyalty as faithfulness to Christ. But when I read her chapter on friendship, everything changed.

As soon as I read these words: “I can’t imagine the process of ‘doing theology’ without the encouragement of the conversation with friends…especially with those people with whom we share our lives over time”, I felt this was for me. I felt this was for me.

I’ve had the privilege of studying theology at Seminary level, attending conferences, listening to hundreds of sermons, and reading books from some of the best theologians out there. However, I would argue that my best theological insights come from informal conversations with friends. Like Bedford says, especially those with whom I’ve shared my life over time. The ones that have been through thick and thin, en las buenas y en las malas.

Inspired by her words, here is my new approach to life and theology through three ideas of friendships: My life of faith as friendship with God and others, the work of theology as God-talk among friends, and the sharing of our faith as extending friendship (ours and God’s) to the world.

My life of faith as friendship with God and others

“I have called you friends,” Jesus said to his disciples (John 15:15). The gospel is not just about being saved from hell and for heaven. It is not just about our sins being forgiven and being given a second chance. The gospel is about being reconciled to God and to one another. That means we can define our life of faith as friendship with God. All because of Jesus.

Paraphrasing the church fathers, Bedford puts it like this: “the Son became our friend so that we could become friends of God”. “Jesus is the friend whose love gives life to the beloved providing intimacy with God that can be called friendship with God”, she also says.

She warns against the danger of privatizing or individualizing our friendship with Jesus. “His words are not to be taken as invitation to a privatized or individual friendship, but to express the context of a community of friends that also relate among themselves with Jesus”. This means our shared friendship with him allows for us the potential of being friends. To belong to a community of friends.

When Paul talks about the ministry of reconciliation, he binds being reconciled with God with being reconciled with one another. Just as Jesus reaffirmed the relationship between loving God and loving our neighbor.

In his book, He Calls Me Friend, author and activist John Perkins reflects on the role of friendship in his life and its potential to change the world. It all begins with a God who, from the beginning, shows us the way. Looking back at his experience of reading the Bible, he says: “I read about a God who would be a friend”. He also relates our creation as a product of that relationship in the Godhead: “I’m pretty sure we were birthed out of the friendship of the Trinity.”

In that sense, we could say God exists in friendship, creates out of friendship, and invites us into friendship (one that is everlasting). In Perkins's words: “Friendship is discipleship in action.” That’s our life of faith.

The work of theology as God-talk among friends

If we consider our life of faith as friendship with God, “What does it mean for theology?” Bedford asks. She immediately answers: “Theology can be seen as an exercise in gratitude for God’s friendship, carried out in friendship with others.”

In other words, theology is possible because of our friendship with God, and it becomes articulate in the context of friendships with others. Theology is not for the isolated intellectual in a closed room full of books.

If theology happens only in a textbook or in a seminary class, then it is exclusively for those who have access to those resources (a vast minority). But if theology happens in the conversations between friends, then it’s part of lo cotidiano, the everyday lives of people of every background, race, gender, and generation.

The book of Job rarely comes up in conversations about friendship. If it does, it is usually to talk about the poor choices Job had made in his circle of friends. But a careful reading of the story reveals something else.

As the story goes (Job 2:11-13), as soon as Job’s friends heard about his tragedy, they traveled, and then sat in silence for seven days at his side. Friendship is more about presence than about words, and sometimes sitting in silence is the best thing a friend can do.

As Bedford says:

“Meaningful conversations with friends likewise allows an embodiment of our ideas, as we gesticulate and articulate, giving voice to what otherwise would remain silent. Even sitting in silence together does not allow for a disembodied silence: we breathe, exchange glances, feel each other’s company, and come away from the encounter subtly changed.”

Job’s friends didn’t stay silent, and many believe that was a mistake. “Calladito te ves más bonito,” some would say. But even if we can agree that they didn’t speak well (God settles that clearly in the text), they were doing theology. And doing theology is not always just about being right, but about the struggle to understand the mystery of the divine.

We could argue that they were wrong in some of their assumptions and conclusions, but still they showed up and wrestled with the situation with the knowledge and tools they had. They were present. I would even argue that Job needed that interaction, even if painful, to process his own pain and his understanding of God. In other words, it was precisely through his listening to their arguments, and his struggles with his own thoughts, that he was able to articulate his own ideas and questions, and in doing so, he met God like never before.

But it all started with a group of friends talking about God. For Job and his friends (and for many of us), theology is not an abstract study. It is about real life, right here, right now. It is doing theology con los pies en la tierra.

Sharing our faith as extending friendship (ours and God’s) to the world

Finally, we get to the idea of sharing our faith as inviting the world to friendship, with God and us. If we truly believe that we have been sent to the world, just as Jesus was sent by the Father (John 20:21); and if we understand Jesus’ saving work as becoming our friend so that we could become friends of God; then it would make sense that our proclamation of the good news is wrapped in an invitation to friendship.

In a way, loving our neighbors translates to being a friend to those around us. That’s what the “good Samaritan” does in the widely known story told by Jesus (Luke 10). The Samaritan did nothing else than treat the other as a friend. And we are called to do the same. His ‘goodness’ comes as friendship. He treated this stranger the way he would’ve treated a friend. He was a good friend. So we could say that when Jesus calls us to love our neighbors, he’s actually saying, “be a friend”.

Even going back to the Old Testament, where we see a lot more strict rules about relationships with other nations, Jeremiah reminds the people in exile of the plans God has to prosper them (29:11), and they are instructed to settle down in Babylon, build houses, plant gardens, and even marry! I don’t think it would be a stretch to say God was giving them permission, and even calling them to befriend the Babylonians.

In Jesus, God settled once and for all his plan to become our friend. Now he calls us to do the same.

To think that our friendship with others could lead to their own friendship with God is nothing short of a miracle. And if Jesus becoming our friend had the power to change the course of history, what could our befriending others still do today?

About Oscar García

Oscar is a Puerto Rican pastor and international worker with the Christian & Missionary Alliance. He earned a Master of Divinity from Alliance Theological Seminary in New York. Currently, Oscar serves as professor and Academic Director for SeTAU, a theological seminary in Uruguay. He is passionate about learning to read and interpret the Bible with the global church. Oscar enjoys drinking coffee, reading theological books, doing jigsaw puzzles, and playing basketball. He is married to Charlotte and has two daughters, Sofía and Sara. They live in Montevideo, Uruguay.

Articles like this one are made possible by the support of readers like you. Donate today and help us continue to produce resources for the mestizo church.